Introduction

David Jaffee

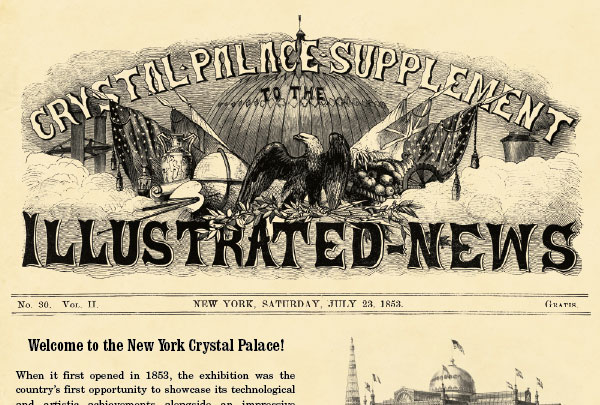

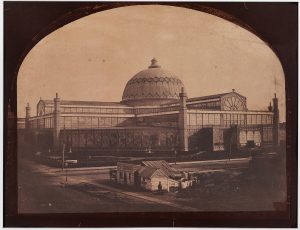

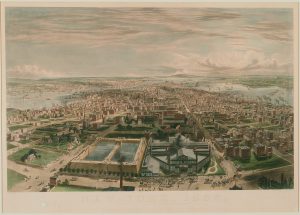

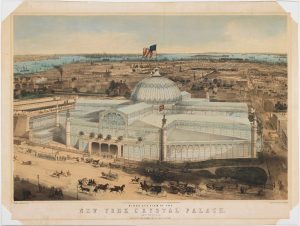

On the far reaches of an increasingly metropolitan New York stood the Crystal Palace, as shown in artist and engraver John Bachmann’s lithograph Birds Eye View of the New York Crystal Palace (fig. 1). Formally known as the Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, the first world’s fair held in the United States in 1853 was based on the London Crystal Palace and similarly housed in an impressive cast iron, steel, and glass structure on the current site of Bryant Park. The gleaming white building, which gave both the fair and the building its nickname, as it had in London, was capped by a dome and waving flags of other nations, all topped by the U.S. flag at the summit.

Fig. 1 John Bachmann. Bird’s Eye View of the New York Crystal Palace and Environs, 1853. Hand-colored lithograph. Museum of the City of New York. The J. Clarence Davies Collection. Gift of J. Clarence Davies, 1929.

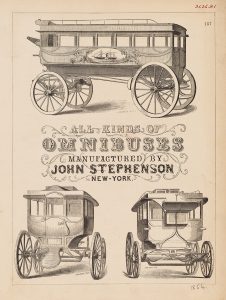

Bachmann, the Swiss-born artist, brought with him to New York his European training in lithography, the dramatic new mode of mass-producing images, along with his exploration of bird’s eye views; he worked in Paris on low altitude bird’s eye views before arriving in 1849 in New York, where he produced New-York, a full-scale view of the city looking south all the way to the harbor from above Union Square. His depiction of the wide city streets with their bevy of vehicles scooting in all directions appeared prominently in his Crystal Palace view. The foreground dominates as the rest of the city recedes; this is the city as transportation hub: horses with riders prance past and others draw private carriages and pubic omnibuses that bring visitors to the north entrance of the exposition, while the harbor is filled with sailing and steam ships, all evidence of the city as metropolis. To the left stands the Croton Reservoir, which opened in 1842 to great fanfare as one of the city’s grandest achievements to date, an engineering marvel bringing the city’s residents fresh water from the north down to the Egyptian Revival reservoir structure, providing a space dotted with promenading New Yorkers.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, New York had staked out its claim as the leading American metropolitan center of commerce and a worthy cultural competitor to Europe by hosting the fair. World’s fairs, starting with the London Crystal Palace of 1851, along with industrial expositions, became a major form of international industrial and cultural competition in the second half of the nineteenth century and on into the twentieth century, drawing culture-seeking international tourists. Residents too flocked uptown to gawk at each other and see the latest mechanical innovations. The Crystal Palace both borrowed from and contributed to the rise of display spaces that promoted sites of urban spectacle, such as P. T. Barnum’s American Museum (1841–65) and A. T. Stewart’s Marble Palace dry goods store, which opened in 1823 (fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Interior of A. T. Stewart’s Astor Place Store, ca. 1880s. Engraving. The New-York Historical Society, Bella C. Landauer Collection.

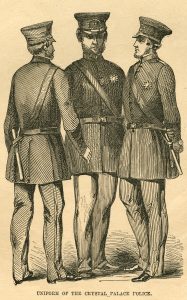

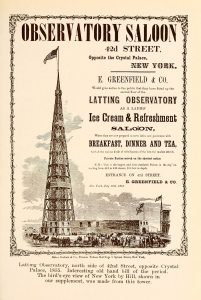

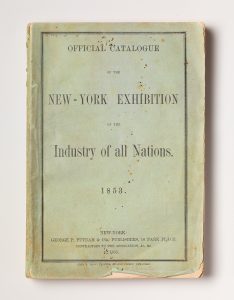

The digital publication for New York Crystal Palace 1853 is based on a 2017 Focus Gallery exhibition at Bard Graduate Center that emphasizes the experience of those who entered the Crystal Palace through the objects they may have seen. The works on display are interpreted through digital components, such as interactive exhibits in the gallery and audio tours for visitors. Bard Graduate Center’s exhibition offers a wealth of visual materials. An opening display offers a brief discussion of the London Crystal Palace exhibition and the struggles of New York’s elite to organize an expensive exposition on this side of the Atlantic, without governmental financial sponsorship. Exterior views trace the building competition, the slow progress of construction, and, after opening day passed, the experience of trekking uptown and making one’s way through the cluster of drinking establishments and public amusements to the fair’s several entrances. Well-known city guidebook authors, such as George G. Foster, quickly revised their popular offerings by adding a visit to the Crystal Palace as a must-see site for visitors to the city, while also highlighting the sensational aspects of urban commercial culture: “For some blocks we have been aware, by the accumulation of coffee houses, grog shops, ‘saloons,’ peep-shows of living alligators, model-artists and three-headed calves, that we were approaching the newly discovered, Sedgwickean centre of the metropolis. ‘Fortieth street, Crystal Palace’—says the conductor, stopping the cars handily on the crossing.” The Focus Gallery exhibition attempts to contrast the chaotic commercial culture of the exposition’s environs with its far more sedate interior, which provided a mock world in miniature in which, according to historian Dell Upton, “the combination of order and profusion implied totality”; the exhibition “combined rational organization with picturesque presentation” and provided an opportunity to engage in limitless consumption.

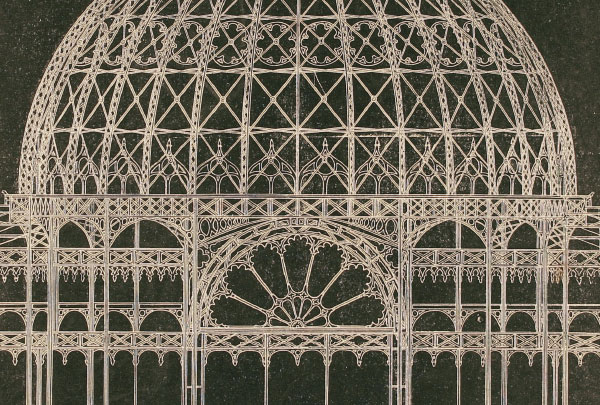

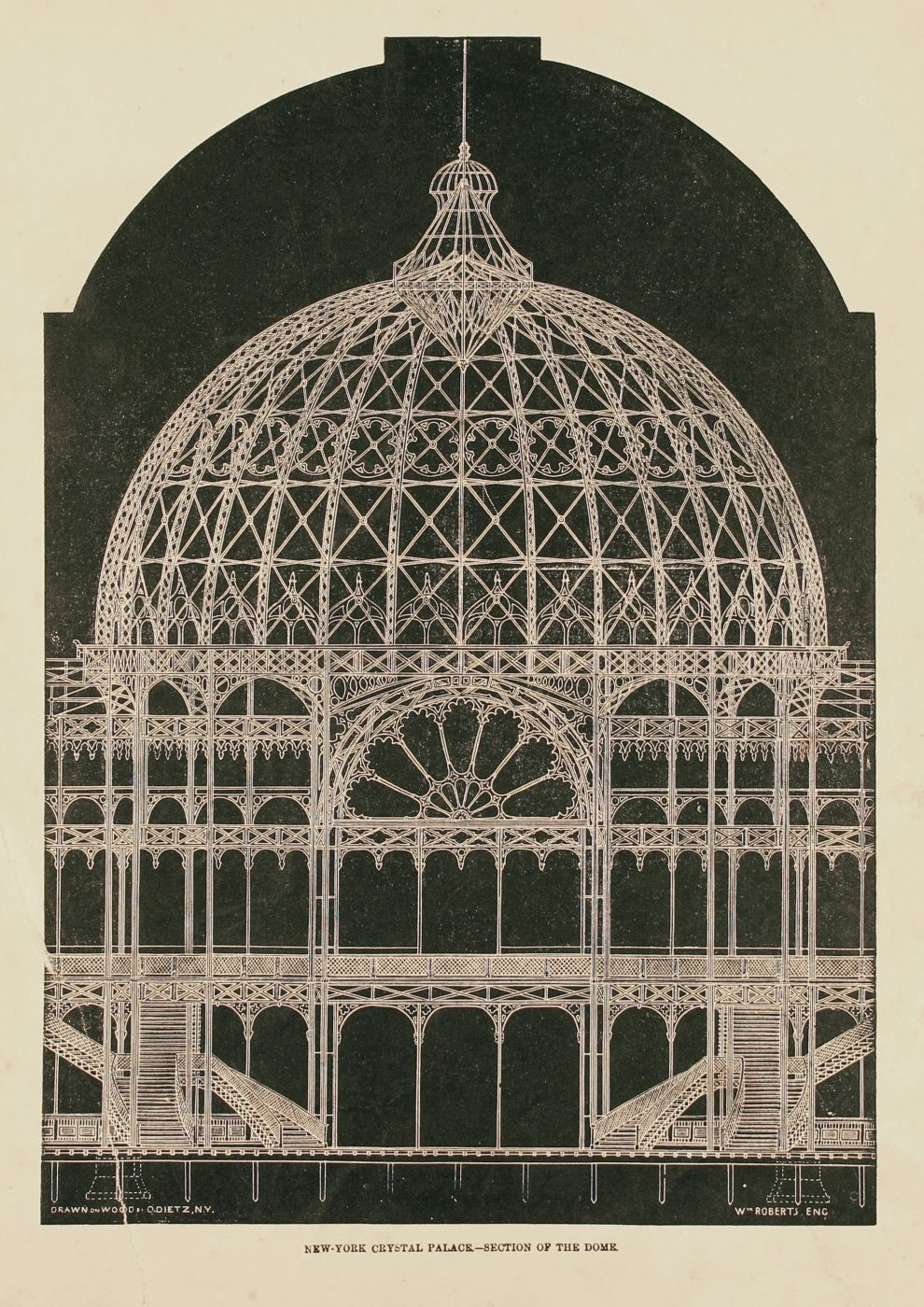

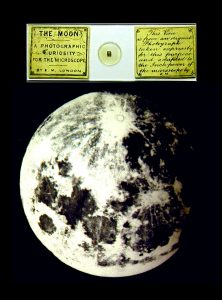

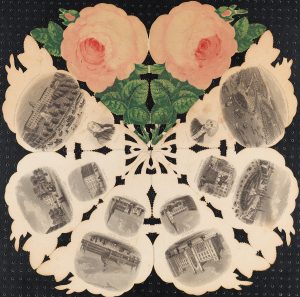

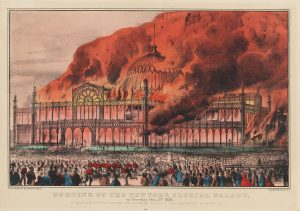

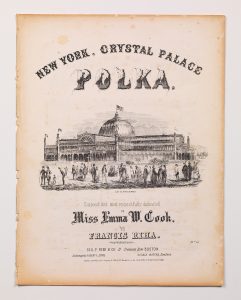

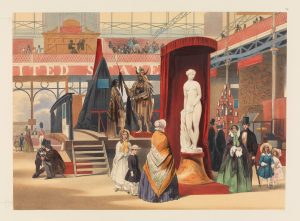

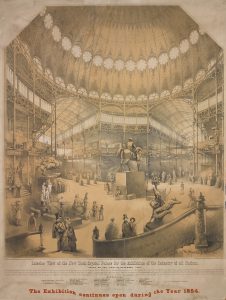

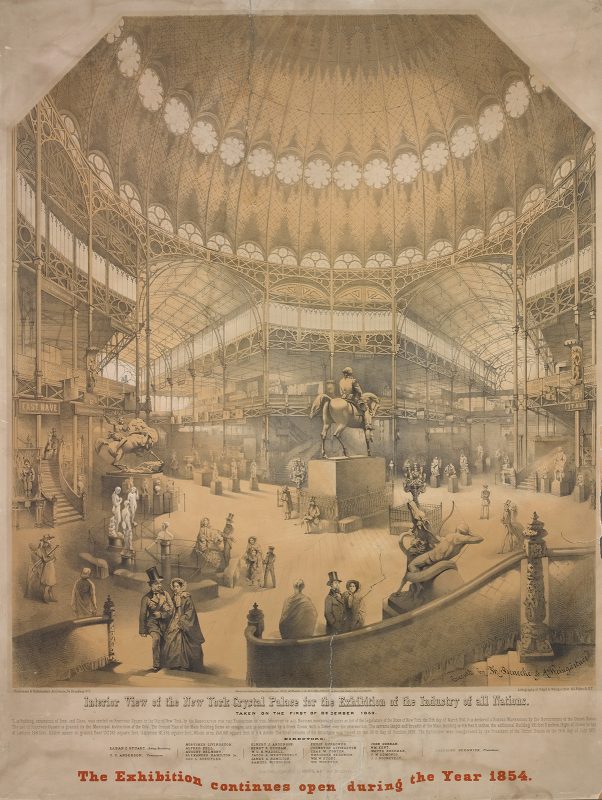

A turnstile, an image of which is reproduced in the exhibition, marks that boundary as visitors enter the interior gallery. As Putnam’s Monthly proclaimed to its readers, the vision that greeted the visitor was “at first a dazzle; light and movement undistinguishable for a while; then, as the eye settled, order emerging here and there; beautiful forms and colors developing themselves one by one; vast climaxes of Art, Industry, and Invention, extending away and away in long perspective on every side; . . . whole avenues of wonders, distracting choice; . . . we look, on all sides, down radiating lines of display, in which various national emblems and devices suggest the world-wide interest of an Industrial unity.” Inside the gallery, a reproduction of a three-foot-tall, grand color lithograph published by Goupil & Cie (fig. 3) evokes the experience of being under the dome of the Crystal Palace. One of the more popular exhibits was the Crystal Palace’s sculpture gallery, which brought an internationally renowned sensation, Hiram Powers’s The Greek Slave, to American audiences after it had been exhibited in London and many other cities. The life-size statue is represented by a scaled-reproduction in Parian ware that demonstrates how expensive large-scale sculptures were made available for entry into American middle-class parlors and represented their owners’ embrace of taste and culture. European-trained furniture makers brought their skills and cachet to the New York furniture trade, which offered the expensive upholstered parlor furniture such as Prussian immigrant Julius Dessoir’s chair (fig. 4). Even with the popularity of such exhibits, American technology took pride of place at the Crystal Palace with the display of such well-known exports as Isaac Singer’s sewing machine as well as the work of the more than forty American daguerreotype makers. Another section of the gallery exhibition features souvenirs, including such utilitarian objects as a bottle of soda water and a folded paper souvenir, in which the image of the Crystal Palace joins those of notable buildings, such as Trinity Church and Barnum’s American Museum. The Focus Gallery exhibit closes with a piece of fused glass from the remains of the well-publicized fireproof iron-and-glass building that, ironically, burned to the ground in 1858.

Fig. 3 Interior view of the New York Crystal Palace for the exhibition of the industry of all nations. Taken on the first of December 1853 . . . Cartstensen & Gildemeister architects, 74 Broadway N.Y. 1853. Color lithograph by Nagel & Weingärtner. Published by Goupil & Cie. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, Print Collection, New York Public Library.

Fig. 4 Julius Dessoir. Armchair, 1853. Rosewood, replacement showcovers. Gift of Lily and Victor Chang, in honor of the Museum’s 125th Anniversary, 1995, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995.150.2

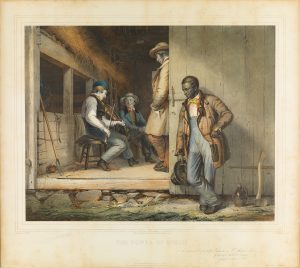

Bard Graduate Center’s exhibition seeks to demonstrate the intense visuality of mid-nineteenth-century New York, whether on the streets of the city, which were festooned with banners, flocked with pedestrians, and punctuated with store windows, or within the Crystal Palace, with its abundant display of commodities and eye-catching interiors. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine made this connection in its description of Broadway: “when it is completed [it] may pass for the three-miles-long nave of a Crystal Palace, for admission which no charge is made.” Indeed, the exhibit attempts to recapture the urban spectacle that captivated guidebook writers and travelers, whose accounts featured vivid descriptions of Broadway that palpably relayed the visuality and spectacle of the metropolis’s central thoroughfare. “It is a perfect Kaleidoscope,—each day presenting some new feature of change,” Frederick Saunders wrote in New York in a Nut-Shell. Cornelius Mathews’s Pen-and-Ink Panorama of New-York City opens with an invitation to his readers to accompany him on “a panoramic exhibition,” as he “paint[s] a home picture” of the city, beginning with Broadway, “a great sheet of glass, through which the whole world is visible as in a transparency”—echoing other writers in seeing the street as the microcosm of the city, the nation and, indeed, the world. Mathews ends his panorama with another new visual wonder of the age, a “Bird’s-eye View of New York.” In words and especially in images, these writers and graphic artists, publishers and printers, were convinced that the nineteenth-century city could only be captured and understood in visual terms.

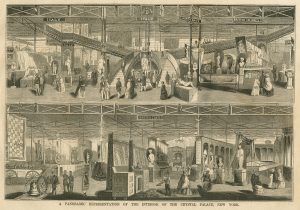

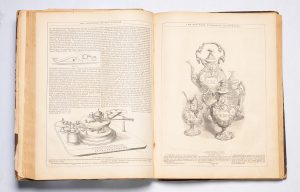

This Focus Gallery exhibition makes great use of the wood engravings of the illustrated press and the colorful lithographs of artists such as John Bachmann and firms such as Currier & Ives, “Printmakers to the People,” as they called themselves. “The middle decades of the nineteenth century marked a watershed in the development of a mass market for images in the United States,” Michael Leja has written, with the “high-volume technologies of lithography and electroplated wood engraving” leading the way. Woodcuts, one of the oldest print techniques, made illustrated periodicals into a mass-market phenomenon, and the Crystal Palace was a prominent subject from the very beginning of its construction to the building’s fiery collapse in in 1858. Wood engravings varied from soaring vertical depictions of the domed interior, such as those that appeared in Gleason’s Pictorial, to horizontal panoramas that captured much of the interior (fig. 5), with well-clad visitors gazing at the sculpture or examining the United States exhibit. “The ‘illustration’ mania is upon our people,” Cosmopolitan Art Journal wrote in 1857, when Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper was five years old and Harper’s Weekly had just been inaugurated. The relative ease of production of lithography, in which an artist drew on a stone with grease crayons, allowed for larger and less expensive runs than were possible with metal plates. Genres such as bird’s eye views and panoramas provided ways of capturing the immensity of new urbanscapes or vast interiors for lithographs and wood engravings alike. Examples can be found in the Focus Gallery exhibition. Finally, photography in the form of the unique silvered images of the daguerreotype was a prominent feature of the exposition, but photographers such as the French-born Victor Prevost adopted the emerging technology of paper photography, and the rapidly popular commercial makers of stereoviews, such as E. & H. T. Anthony, found the exterior of the buildings and the interior displays to be compelling.

Fig. 5 Frederick J. Pilliner. A Panoramic Representation of the Interior of the Crystal Palace, New York. A panoramic Gleason’s Pictorial, Boston, Saturday, February 4, 1854. Wood engraving on newsprint. Collection of the author.

Bard Graduate Center students helped to develop the object list and refine the interpretation of the objects on view. They worked on designs and content for the two digital interactive exhibits in the gallery and the three audio tours and wrote the essays that are the basis of this digital publication. The essays explore how the fair represented a new kind of urban spectacle and took advantage of new visual technologies, such as the daguerreotypes and lithographs that were exhibited and promoted at the Crystal Palace. These new visual technologies were part of the vast publicity apparatus of the mid-nineteenth-century world of print that brought notice of the Crystal Palace to all corners of the United States. Although the Crystal Palace did not achieve financial success, it did promote the visibility of American artists and inventors and advanced the development of uptown Manhattan.

The official title of London’s Crystal Palace exhibition, held in 1851 in Hyde Park, is The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations.

See Hannah Wirta Kinney, “John Bachmann’s New York,” in Visualizing 19th-Century New York http://visualizingnyc.org/essays/john-bachmanns-new-york/.

George Foster, Fifteen Minutes around New York (New York: DeWitt and Davenport, 1854), 23.

Dell Upton, “Inventing the Metropolis: Civilization and Urbanity in Antebellum New York,” in Art and the Empire City: New York, 1825–1861, ed. Catherine Voorsanger and John K. Howat, 41 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000).

“The Great Exhibition and Its Visitors,” Putnam’s Monthly 2 (December 1853): 579.

David Henkin, City Reading: Written Words and Public Spaces in Antebellum New York (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998).

“Editor’s Easy Chair,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 7, no. 37 (June 1853): 129–30

Frederick Saunders, New York in a Nut-Shell (New York: Strong, 1853), 101.

Cornelius Mathews, Pen-and-Ink Panorama of New-York City (New York: Taylor, 1853), 5.

Ibid., 203.

Michael Leja, “Sculpture of a Mass Market,” in John Rogers: American Stories, ed. Kimberly Orcutt, 11 (New York: New-York Historical Society, 2010).

See Virginia Fisher, “From the Second Empire to the Empire City: Victor Prevost’s Architectural Views, 1854–56,” in Visualizing 19th-Century New York, http://visualizingnyc.org/essays/from-the-second-empire-to-the-empire-city-victor-prevosts-architectural-views-1854-1856, and Virginia Spofford, “Prosperous Partnership: Edward and Henry Anthony’s Production of ‘Instantaneous Views,’” in Visualizing 19th-Century New York, http://visualizingnyc.org/essays/prosperous-partnership-edward-and-henry-anthonys-production-of-instantaneous-views/.