“And the Silver Medal goes to…”: Awards at the New York Crystal Palace

Ana Estrades

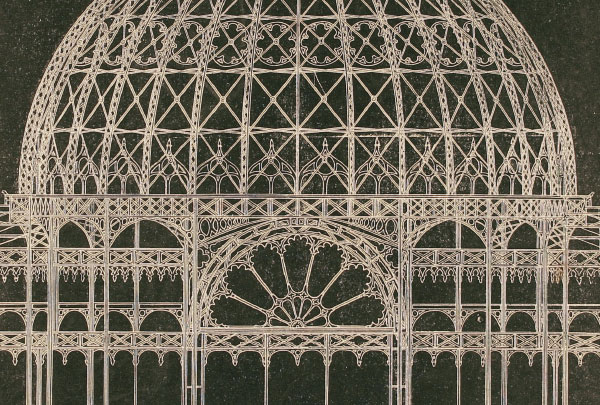

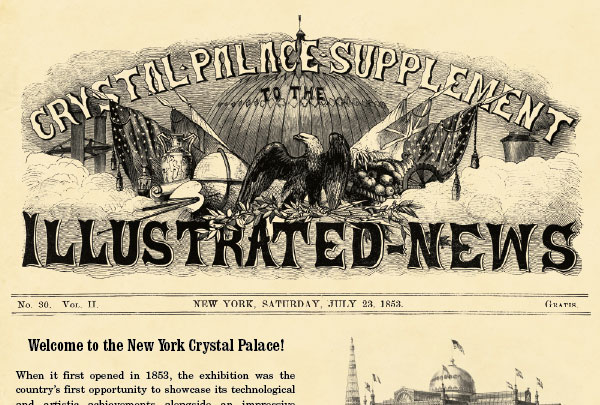

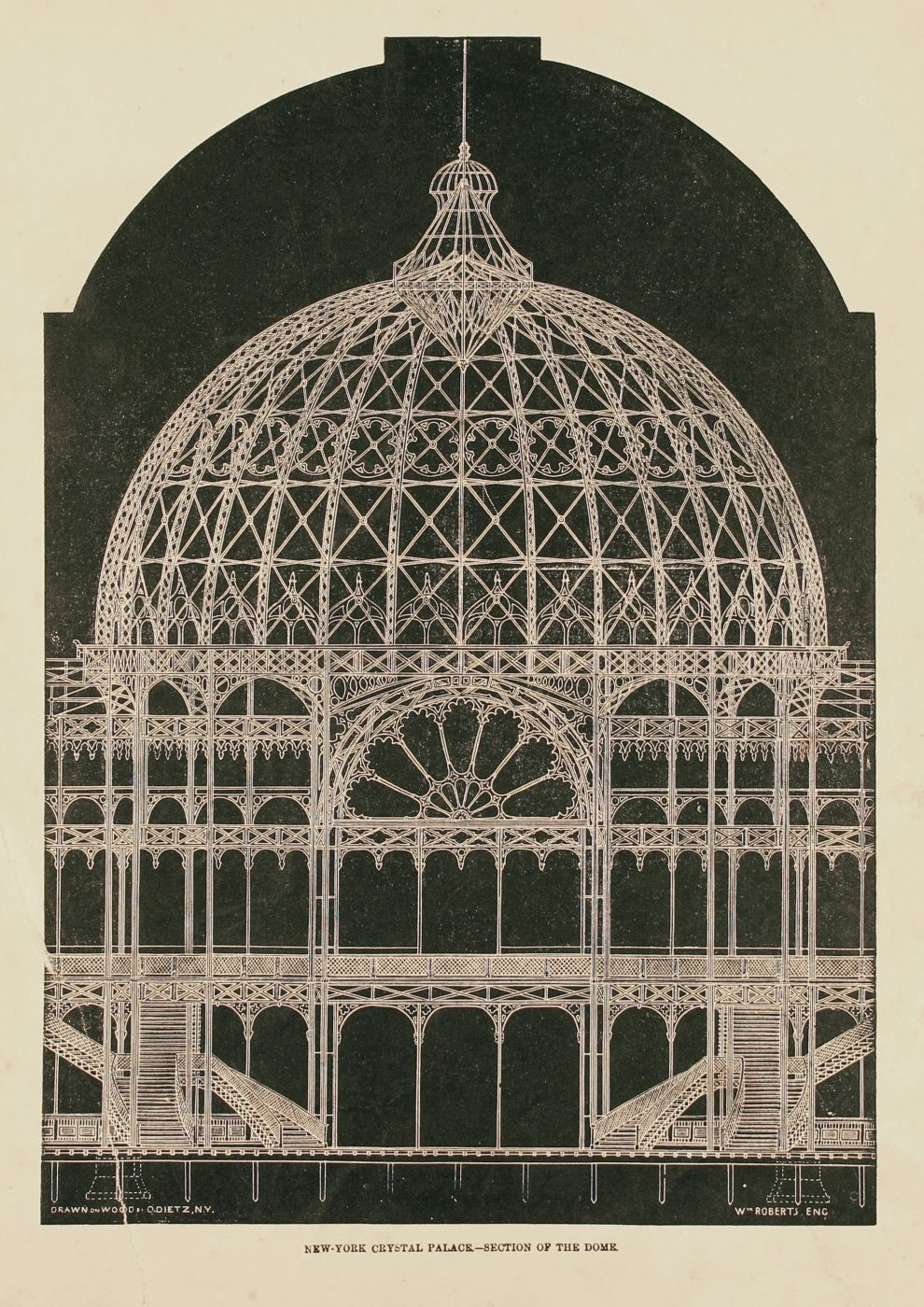

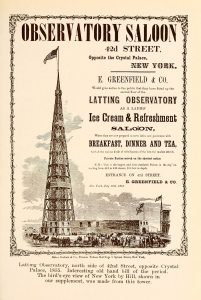

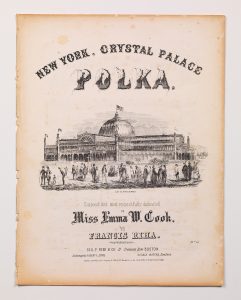

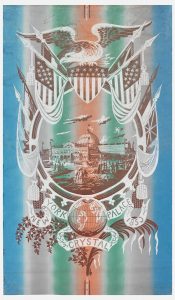

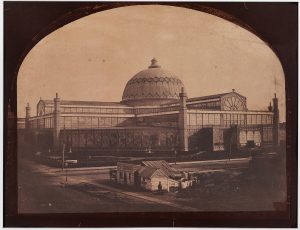

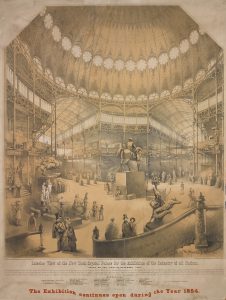

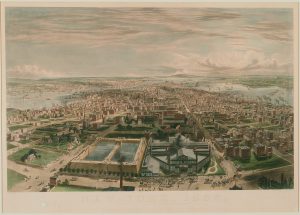

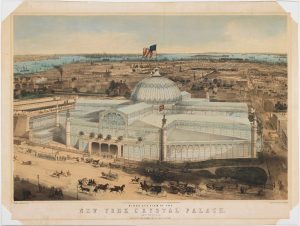

To commemorate the 1853 Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in New York, thousands of medals were struck with the familiar iconography of the fair: flags of the exhibiting countries, allegorical figures holding attributes of industry, structures such as the Latting Observatory. But the most iconic, and ubiquitous, of all the symbols was the Crystal Palace building itself. Engraver Anthony C. Paquet created a particularly skillful rendition of the glass and iron structure in white metal (fig. 1). In the medal, Paquet gave dimension to the building, with its central dome, flags, crowds outside, and also provided information about the construction, including the names of the architects.1 Georg Carstensen and Charles Gildemeister received the highest award, a silver medal for the design of the glass and iron structure that hosted the fair from July 14, 1853, to November 1, 1854. Because no gold medals were awarded at the fair, the silver medal was given only for originality of design, invention, or discovery, coupled with skill of fabrication and excellence of material.2 The organizers and juries of the awards followed the precedent of the Great Exhibition in London, where there were two classes of medals—silver and bronze—and an honorable mention.3 In New York, a total of 115 silver medals were awarded; 1,186 bronze medals; and 1,210 exhibitors received an honorable mention.4

Fig. 1 Anthony C. Paquet. Medal, 1853. Obverse: GEORGE WASHINGTON UNITED STATES OF AMERICA; reverse: THE CRYSTAL PALACE FOR THE EXHIBITION OF THE INDUSTRY OF ALL NATIONS NEW YORK 1853 | PRESIDENT THEODORE SEDWICK ARCHITECTS|MESSRS CARSTENSEN and GILDEMEISTER LENGHT 365 FEET WIDTH 365 FEET HEIGHT OF DOME 148 FEET GLAZED SURFACE 206,000 SUP FEET OCCUPIES ACRES OF GROUND. White metal. Courtesy of the American Numismatic Society, 1940.100.1005.

While precious materials, silver and bronze, were reserved for the awards, the more striking difference between the commemorative and the award medals is in the iconography. The commemorative medals always include an image of the Crystal Palace building on one side, whereas the award medals depict a group of allegorical figures and the legend “Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations New York 1853” within a laurel wreath on the reverse (fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Charles Wright and J. A. Oertel Del. Silver medal, 1853. Reverse: EXHIBITION OF THE INDUSTRY OF ALL NATIONS NEW-YORK 1853. Silver. Courtesy of the American Numismatic Society, 1887.24.2.

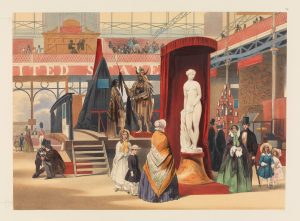

Laurel wreaths also appear on Greek and Roman medals and coins. In ancient Greece, laurel wreaths were awarded to victors, and Romans used wreaths to crown their emperors. The three draped figures in the medal are a crowned and winged god, probably Apollo, holding the hand of Industria, who is kneeling on the ground to receive a laurel wreath from the city of New York, distinguished by her mural crown. These figures represent the alliance of art and industry in the exhibition—the arts symbolized by the god Apollo, with Industria awarded with the laurel wreath. In the following discussion of the awardees at the fair, artistic achievement will be considered alongside technological and material innovation.

In 1853, the Association for the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations published the official awards for the most deserving contributors at the New York Crystal Palace.5 Through the publication, it is possible to know not only who and what was exhibited but also why the medals were awarded. This essay will focus on two silver medalists, Tiffany & Co. and Brooklyn Flint Glass Works, which, in their respective categories, precious metals and glass, epitomize the artistic and material achievement at the Crystal Palace, and on a recipient of an honorable mention, Fitzgibbon’s daguerreotype business.

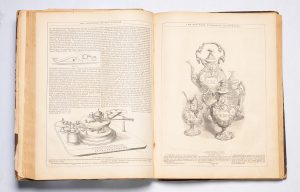

The most prestigious jewelry house in United States was originally known as Tiffany, Young & Ellis. It was renamed Tiffany & Co. when Charles Lewis Tiffany took sole control over the company in 1853, the year of the Crystal Palace exhibition.6 A commitment to excellence in materials, design, and manufacture soon led to the firm’s popularity and success. At the Crystal Palace, Tiffany won a silver medal “for elaborately wrought Classical Silverware and Jewelry of superior design and execution.”7 A fine example on display at the fair was an intricate set, or parure, of seed-pearl jewelry (fig. 3), including a bracelet, a necklace with a cross pendant, earrings, and a brooch. The very small seed pearls were imported from India through Paris and strung in New York in a design that added dimension.8 Around the middle of the nineteenth century, when the United States was rapidly developing its own technology, design, and craftsmanship, Tiffany’s reliance on imports was also declining as they developed their own expert workshops.

Fig. 3 Specimens of strung pearls on exhibition at the Crystal Palace. From Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, December 24, 1853, 412.

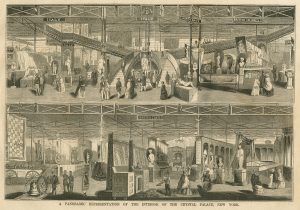

The Brooklyn Flint Glass Company, or Works as it was sometimes called, won not one but two silver medals in the glass-manufacturing category “for their discovery in compounding materials, by which a superior brilliancy of color is produced.”9 The World of Science, Art and Industry, recounted the company’s ongoing experimentation to find out how to remove oxide iron, responsible for the yellow color in the sand, and for giving its green tint to common glass.10 The clarity and brilliancy of Brooklyn’s flint glass is exemplified in a colorless, deep-cut sugar bowl (fig. 4) Its diamond pattern, cut by Joseph Stouvenel who worked for the company, was known to have been on display at the 1853–54 Crystal Palace exhibition (fig. 5).

Fig. 4 Joseph Stouvenel and Company, cutter. Sugar bowl with cover, ca. 1851–57. Manufactured by Brooklyn Flint Glass Works. Colorless lead glass; mold-blown, applied, machine cut. Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. Purchased with the assistance of The Karl and Anna Koepke Endowment Fund, 2016.4.5.

In both the London Great Exhibition of 1851 and the successor fair in 1853 New York, the Brooklyn Flint Glass Company successfully showcased its own cut glassware. A contemporary lithograph (fig. 6) illustrates how the company turned its award in London into an advertising opportunity.11 Below the fanciful display, the London medal award is reproduced, to the left and right of the fountain in the middle. A group of allegorical figures is seen to the left, with Industry kneeling to be crowned by Britannia.12 On the reverse, the London medal features the conjoined profiles of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, as seen on the bottom right of the advertisement.

Fig. 6 Brett & Co., lithographer. The Brooklyn Flint Glass Company Warehouse No. 30 South William Street New-York. Prize Medal Awarded at The Great Exhibition, London, from Charles T. Rodgers, American Superiority at the World’s Fair (Philadelphia: Hawkins, 1852), 57.

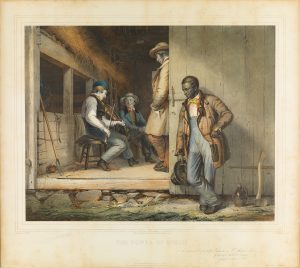

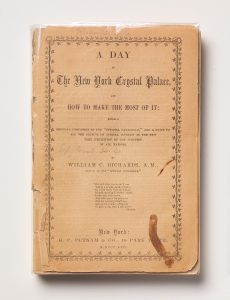

The daguerreotype section was where the United States stood preeminent at the Crystal Palace. Several bronze medals were awarded to daguerreotype exhibitors, showing American mastery of this relatively new art. In his critique of the fair, Horace Greeley claimed that John H. Fitzgibbon had “the richest exposition in the Fair—the most expensive frames, with a large and passable collection.”13 The entrepreneurial daguerreian artist received an honorable mention “for his tableau of elegantly mounted daguerreotypes.”14

Although based in St. Louis, Missouri, Fitzgibbon exploited his participation at the New York World’s Fair by commissioning brass tokens, struck with the image of the Crystal Palace on the reverse (fig. 7). The legend “Fitzgibbon Daguerreotype Gallery” is engraved around the symbolic eagle, while “New York Crystal Palace 1853” is clearly impressed on the opposite side. Sometimes tokens functioned as currency, but this example does not indicate any monetary value, so it must have had a promotional and commemorative function similar to that of the larger official medals, which also bear the iconic Crystal Palace building.

Fig. 7 Brass token of the Fitzgibbon Daguerrerotype Gallery, 1853. Obverse: * fitzgibbon daguerreotype * / gallery; reverse: new york crystal palace / 1853. / * * * * * * * * *. Brass. Courtesy of the American Numismatic Society, 0000.999.57047.

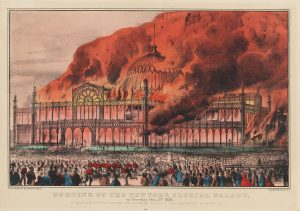

The award medals and honorable mention designation showcase the industrial and artistic achievements of the United States at the New York World’s fair. The silver medal awardees in the categories of precious metal and glass, Tiffany & Co. and the Brooklyn Flint Glass Company, best exemplify the material and industrial innovation on display under the monumental glass- and wrought-iron structure of the Crystal Palace. The distinctions for excellent execution, brilliancy, material luxury, and elegant display are representative of how officials, juries, and visitors must have responded to the sight of such spectacular exhibitions.The medals and tokens of the Crystal Palace, along with a host of popular souvenirs (see essay by Roberta Gorin), have not only outlasted the exhibition and the building that hosted it but also often the technology and the companies awarded. Except for Tiffany & Co., the exhibitors have for the most part disappeared, and daguerreotyping has developed into other forms of photographic reproduction, leaving the medals as iconographically powerful and enduring mementos of the ephemeral world’s fair.

Information on the reverse: the crystal palace for the exhibition of the industry of all nations new york 1853 | president theodore sedwick architects | messrs carstensen and gildemeister lenght [sic] 365 feet width 365 feet height of dome 148 feet glazed surface 206,000 sup feet occupies acres of ground estimeted [sic] value $ 450,000. American Numismatic Society, http://numismatics.org/collection/1940.100.1005.

Horace Greeley, Art and Industry as Represented in the Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in New York 1853 (New York: Redfield, 1853), 14–15.

Greeley, Art and Industry, 11.

“Awards at the Crystal Palace,” Maine Farmer 22, no. 5 (January 26, 1854): 2.

Association for the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations. The Official Awards of Juries (New York: Bryant, 1853), https://archive.org/details/officialawardsof00asso.

Clare Phillips, Bejewelled by Tiffany, 1837–1987 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2006), 8.

“Class 23,” Official Awards, 85.

Phillips, Bejewelled by Tiffany, 13.

“Class 24,” Official Awards, 88.

Benjamin Silliman Jr. and C. R. Goodrich, The World of Science, Art, and Industry, Illustrated from Examples in the New-York Exhibition, 1853–54 (New York: Putnam, 1854), 159.

Charles T. Rodgers, American Superiority at the World’s Fair (Philadelphia: Hawkins, 1852), 57.

Example from the Bard Graduate Center study collection: bronze medal of the London Crystal Palace, 1851223725. Awardee inscribed: Cadwell Payson & Co.

Greeley, Art and Industry, 171–77.

Fitzgibbon exhibited electrotype copies from daguerreotype plates, beautifully executed, in Official Catalogue of the New-York Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, 1853 (New York: Putnam, 1853), 50. The honorable mention is listed under “Class 10,” Official Awards, 37.