Commodities at the Crystal Palace: A Case Study of John Genin’s Spectacular Fashion Display

Clara Boesch

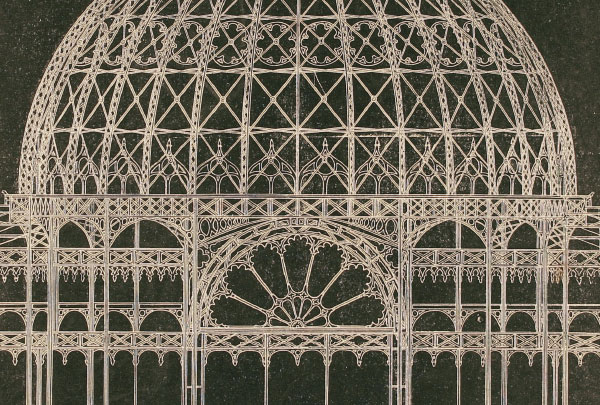

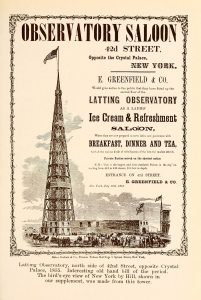

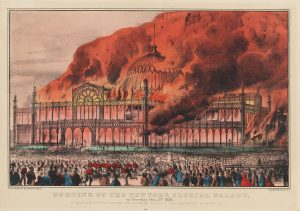

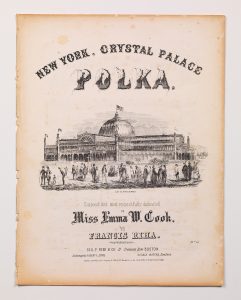

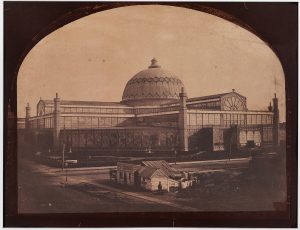

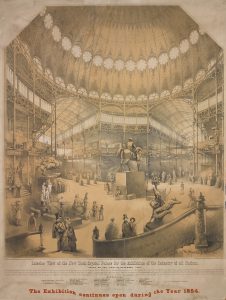

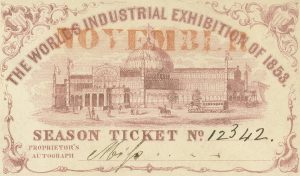

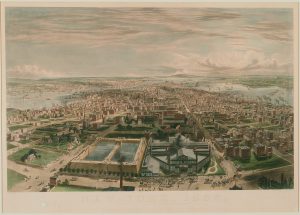

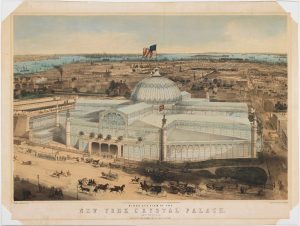

New York’s 1853 Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations at the Crystal Palace, modeled after the successful London Exhibition of 1851, was emblematic of the nation’s growing commercial culture and “society of spectacle.”1 The exhibition was the nation’s first public venue dedicated to uniting, systematizing, and showcasing the world’s material achievements under one roof. Myriad objects were arranged in spectacular displays that captured the attention of local residents and visitors alike. Despite its global mission to edify and inspire the masses with examples of innovation and design, the Crystal Palace exhibition was a monument to the developing commodity-driven culture of New York City. As the rapidly developing “Great Emporium” of the nation, mid-nineteenth-century New York City began to rival London and Paris.2

In the early part of the century, store design was relatively minimal, as shopkeepers stored their stock on shelves behind a counter or in storerooms. Customers would enter a store, inquire about the type of goods desired, and wait for the shopkeeper to retrieve samples for them. In the expanding commodity culture of the mid-nineteenth century, store design was transformed with the advent of large plate glass windows, which prompted shopkeepers to prominently display large varieties of goods to attract shoppers passing by on the increasingly crowded city streets.3

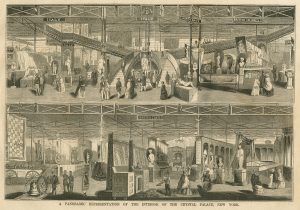

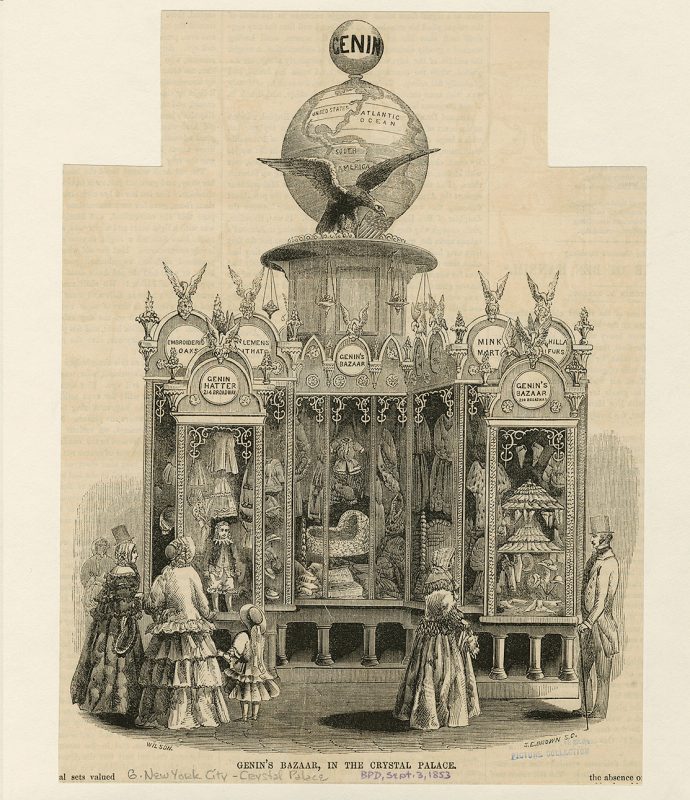

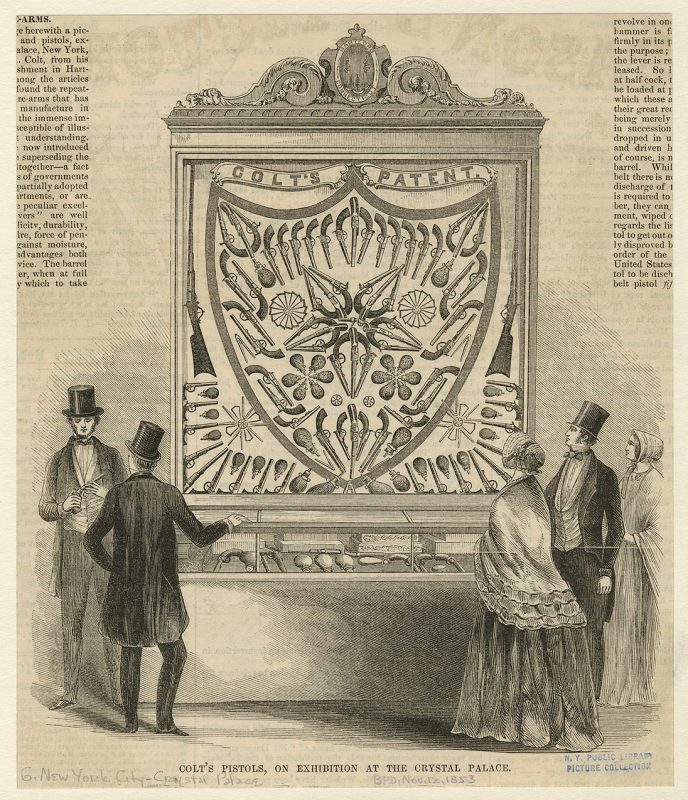

A disproportionately large number of Crystal Palace exhibitors were local manufacturers and retailers. For example, out of twenty-two domestic hat exhibitors in the “Wearing Apparel” class, nineteen were from the New York area.4 Local exhibitors included clothier and hatter John Genin, perfumer Edward Phalon, and firearms manufacturer Samuel Colt (figs. 1, 2, and 3). They adopted the highly visual display strategies of the city’s burgeoning commercial spaces for their eye-catching Crystal Palace displays, arranged so that “even the most mundane article appeared in a novel light.”5

Fig. 1 Wilson, artist; Samuel Brown, engraver. Genin’s Bazaar, in the Crystal Palace. From Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, August 27, 1853. Wood engraving. Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Fig. 2 Wilson, artist; Samuel Brown, engraver. Phalon’s Bower of Perfume, in the Crystal Palace, New York. From Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, August 27, 1853. Wood engraving. Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

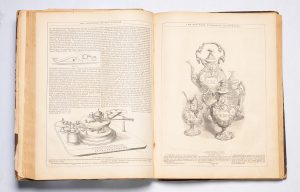

Fig. 3 Wilson, artist; Samuel Brown, engraver. Colt’s Pistols, on Exhibition in the Crystal Palace. From Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, November 12, 1853. Wood engraving. Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

John Genin’s successful clothing shops at 214 and 513 Broadway were spectacular sites of luxury and fashion during the mid-nineteenth century (fig. 4). Genin was an astute businessman who shared a penchant for showmanship with his good friend P. T. Barnum, a man who attracted visitors to his American Museum with infamous publicity stunts. He enticed the public with curious visual spectacles, such as the exhibition of an elderly slave woman named Joice Heth, whom he roused interest in by supplementing doubtful claims that she was George Washington’s 161-year-old nanny with rumors that she was actually a highly realistic automaton. Genin’s extravagant display at the Crystal Palace greeted visitors near the West Forty-Second Street entrance of the exhibition, where it was prominently installed in the center of the north nave next to displays of a fire engine, bells, and marbleized iron.6 An illustrated newspaper remarked on the dominating size of Genin’s display, stating that “with its great size and gorgeous appearance, [it] forms one of the prominent objects in the exhibition. Its dimensions are equal to those of an ordinary parlor, and the colossal globe which overtops the central pediment is conspicuous from all parts of the grand arena.”7 Those who had already visited Genin’s shop at 513 Broadway would immediately recognize the “characteristic” style of the display as “a miniature reproduction of his unique Bazaar in the St. Nicholas Hotel.”8 For visitors who had not been to Genin’s fashionable shops, the shop addresses emblazoned on its showcases assured them that they could later purchase Genin’s goods with a trip down Broadway.

Fig. 4 John William Orr, engraver. Genin’s new and novel bridge, extending across Broadway, New York, 1852. Wood engraving. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

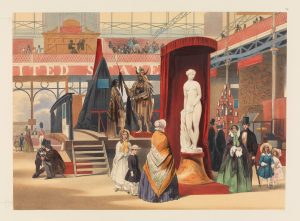

The crowded showcases in Genin’s display encouraged visitors to engage in a “visual pursuit” of his goods.9 Genin’s Crystal Palace display consisted of a central case of infant clothing, referred to as the “Nursery Department,” while to its right were “models of very fine young gentlemen, with every variety of elegant boys’ clothing” (fig. 5) and to the left, “a compartment containing the newest styles of riding habits and hats for ladies.”10 Another section was a “showcase—or rather show room—of furs” that one observer called “the richest . . . displayed in the whole building. The pureness of the royal ermine cape is appropriately displayed over folds of white satin, and the costly sable over dark heavy silks” of a quality “never equaled in this country.”11

Fig. 5 Boy’s forage cap (kepi) and jacket, ca. 1855. Made for Genin’s Bazaar. Hat: silk velvet, ribbon and tassels, glazed kid leather, metal buckle and jet (glass) buttons; jacket: silk velvet and cotton mull with jet buttons. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of Mrs. Ganson Purcell, 1979.228, 229. Photograph © 2017 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Fig. 5

At a time when Parisian fashion dominated the American fashion market, his “temple of trade” proclaimed to Crystal Palace visitors that Genin was an American manufacturer successfully participating in the global fashion arena.12 The giant globe and eagle atop the central showcase were visual symbols that aimed to convince viewers of his international success.13 Ready-made clothing was just beginning to enter the American fashion industry as the nation’s manufacturing capabilities grew. By the mid-nineteenth century, clothing for infants, boys, and men, as well as women’s accessories, such as gloves and mantillas, were frequently produced as ready-made, while women and girls’ complex dresses remained made to measure.14

The ornate cases themselves were praised as being “worthy of [their] superb contents and constantly the center of a crowd of visitors.”15 As “casket[s], which enshrine the gems of fashion from Genin’s Bazaar and Genin’s Hat Store,” the showcases loaded Genin’s products with an air of museum-like preciousness.16 They also functioned much like the large bookcases, sideboards, and buffets that would have held keepsakes, photographs, souvenirs, and ornaments in fashionable domestic parlors of the period. These furniture pieces were specifically designed for consumers to store and display material goods that communicated their tastes and knowledge.

Periodicals such as Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion published detailed images of Genin’s and other exhibitors’ displays (figs. 1, 2, and 3). These illustrations functioned as advertisements that enticed the public to visit the Crystal Palace as well as the shops of its exhibitors. Godey’s Ladies Magazine, a popular women’s magazine of the time, featured Genin’s display in a piece titled “Articles in the Crystal Palace Most Attractive to Ladies,” noting that the nursery department in the display’s central case would be “of particular interest to female visitors.”17 The article credits the visual appeal of the showcase as an attractive force drawing in crowds of women and children viewers:

You are attracted onward by a huge temple, or miniature Crystal Palace. The medallions of the cornice inform you that it is genin’s show-case. The central division is the most attractive to the crowd of ladies and children constantly gathered around it. It is a kind of “Nursery Department,” in which specimens of all that is beautiful and curious in the clothing of children is arranged. The little people go into ecstasies over the large doll, in its white satin high chair, robed in a complete toilet, and, though professedly a “crying baby,” it is now on its best behavior. The little lady on the right is also in elegant costume suited to her apparent age, say three or four years, and between the two is suspended a superb swinging cradle, covered with drawn white satin, and richly lined with the same material, exquisitely quilted . . . fit for no mortal baby.18

Spectacular Crystal Palace displays such as Genin’s and those of other local exhibitors created an illusion of New York’s prosperity and commercial growth. The vast amount of goods on display suggested the profusion of American resources and industry, creating a “myth of the achieved abundant society,” though, in fact, large portions of the population were living in scarcity at this time.19

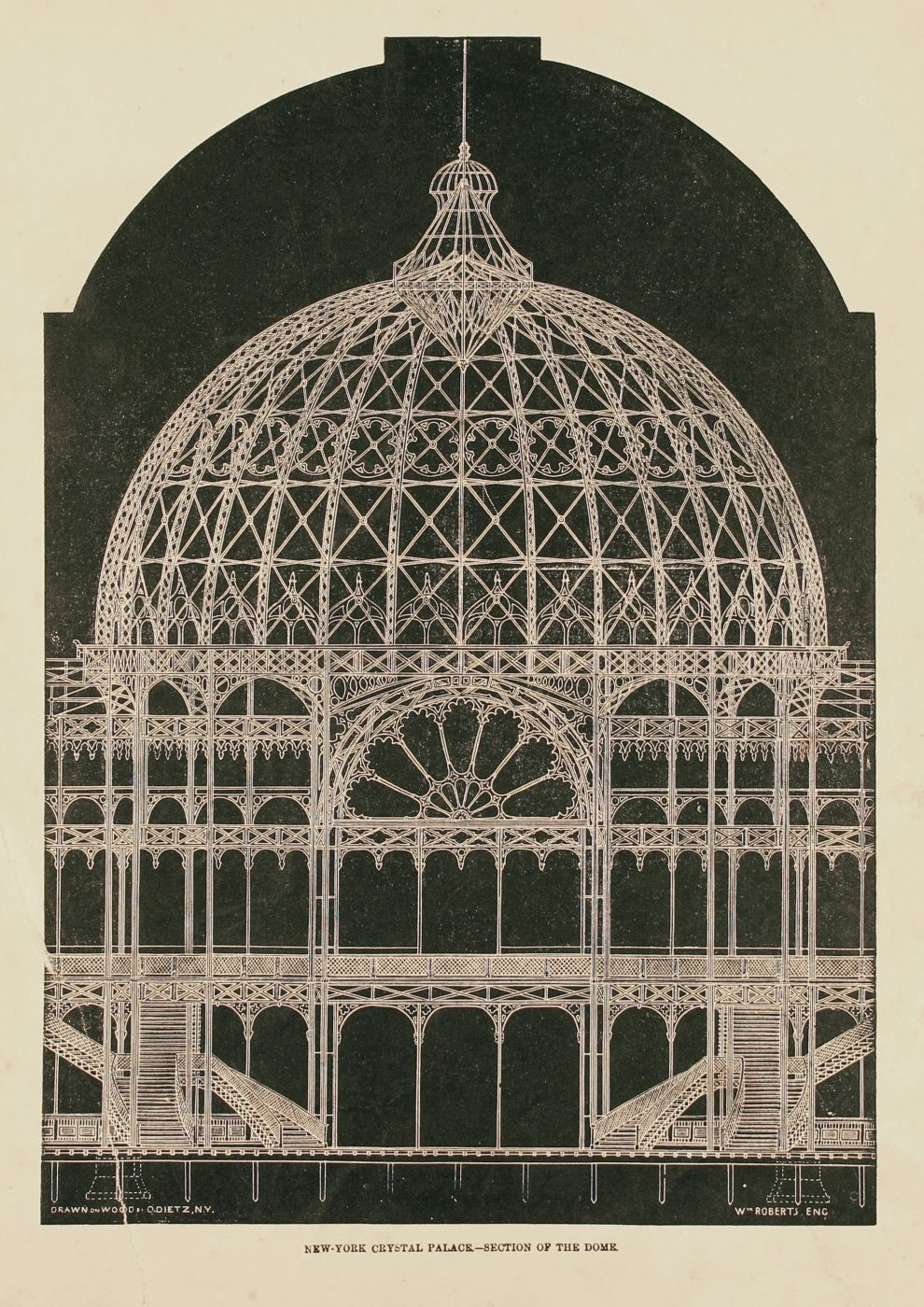

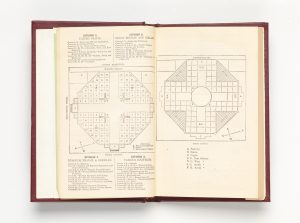

Fig. 6 August Petermann and Karl Gildemeister, designers; printed by August Petermann. New York Exhibition Building, ca. 1852. Wood engraving. Museum of the City of New York. 31.224.12.

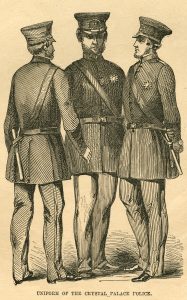

Genin’s extravagant display was accentuated by the atmosphere of the Crystal Palace building itself. The building was constructed from thousands of tinted glass plates that flooded its interior with natural light, which brightly illuminated objects. Constructed with religious architectural references, it also evoked the spiritual aura of early museums.20 Its four intersecting naves were in the form of a Greek cross, lending religious gravity, sobriety, permanence, and an air of history to the ephemeral glass framework (fig. 6). Also like museums, the exhibition employed rope barriers and uniformed officers to prevent visitors from getting too close to objects. These strategies physically distanced objects from visitors, highlighting their preciousness.

Thomas Richards, “The Great Exhibition of Things,” in The Commodity Culture of Victorian England: Advertising and Spectacle, 1851–1914 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1990).

Amelia Peck, “The Products of Empire: Shopping for Home Decorations in New York City,” in Art and the Empire City, ed. Catherine Hoover Voorsanger and John K. Howat, 259–86 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000).

Julia Noordegraaf, “The Emergence of the Museum in the ‘Spectacular’ Nineteenth Century” (Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, 2004), 4.

Official Catalogue of the New York Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, 1853 (New York: Putnam, 1853), 68.

Richards, “The Great Exhibition of Things,” 31.

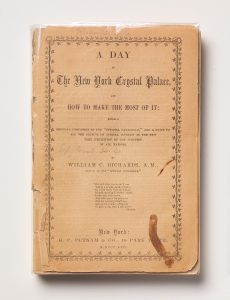

William C. Richards, A Day in the New York Crystal Palace and how to make the most of it: Being a popular companion to the “Official Catalogue,” and a guide to all the objects of special interest in the New York Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations (New York: Putnam, 1853), 23.

Frederick Gleason and Maturin Murray Ballou, eds. Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion 6, no. 1 (January 1854): 152.

Ibid.

Ken W. Parker, “Sign Consumption in the 19th-Century Department Store: An Examination of Visual Merchandising in the Grand Emporiums (1846–1900),” Journal of Sociology 39, no. 4 (2003): 353–71, 360.

Gleason and Ballou, Gleason’s Pictorial Drawingroom Companion, 152.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Louisa Iarocci, The Urban Department Store in America, 1850–1930 (Surrey, U.K.: Ashgate, 2014), 74.

Parker, “Sign Consumption,” 360.

Umberto Eco, “A Theory of Expositions,” in Travels in Hyperreality (Boston: Harcourt Brace, 2014), 292.

“On Articles at the Crystal Palace Most Attractive to Ladies,” Godey’s Lady’s Book 7 (October 1853): 378.

Ibid.

Richards, “The Great Exhibition of Things,” 66.

Carla Yanni, Nature’s Museums: Victorian Science and the Architecture of Display (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 81.