In Remembrance of Things Past: Souvenirs of the Crystal Palace

Roberta Gorin

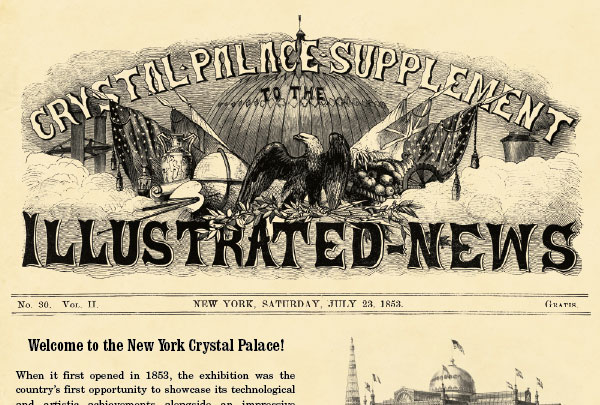

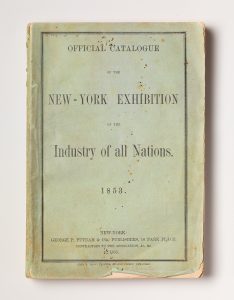

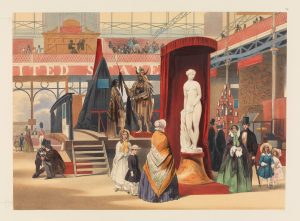

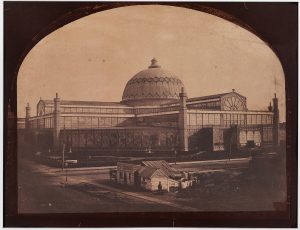

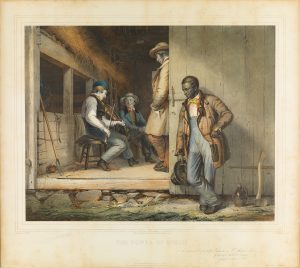

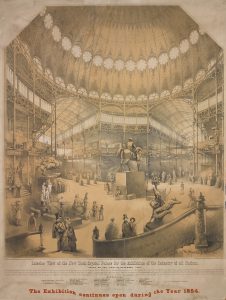

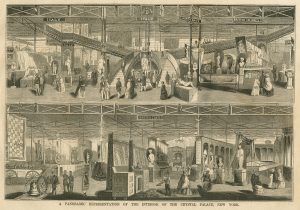

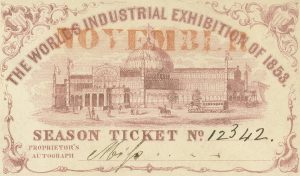

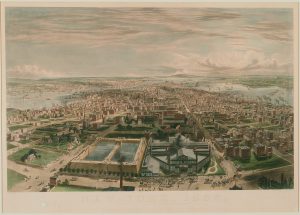

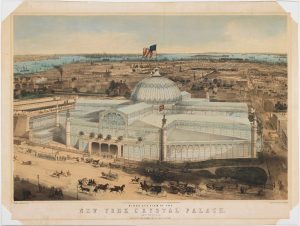

For the United States, a relatively young nation eager to establish its reputation as a manufacturing power and a cultural sophisticate, the 1853 New York Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations represented its entrée onto the world’s stage as a nation of goods. A direct response the staging of the 1851 Great Exhibition in Hyde Park—known as the London Crystal Palace—New York’s own Crystal Palace was an expensive and disruptive public performance on an international scale of all that American industry had to offer.1 Its construction beside the Croton Reservoir, at Sixth Avenue and Fortieth Street—then the uppermost reaches of Manhattan—was subject to many delays; it initiated a series of changes on the physical landscape of the city, from the development of new modes of public transportation to the building of “frail looking wooden structures” in the immediate vicinity for temporary stores, as well as accommodations for the thousands of visitors expected to attend the exhibition.2

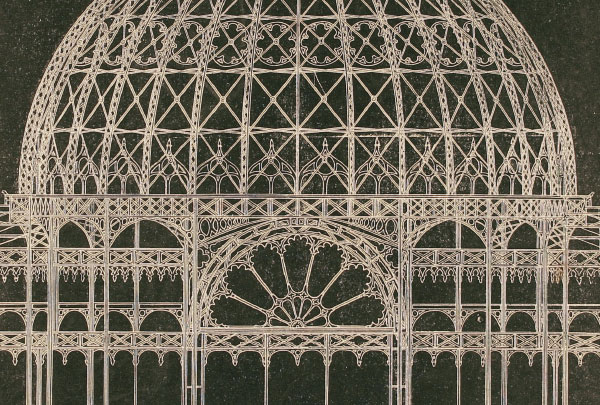

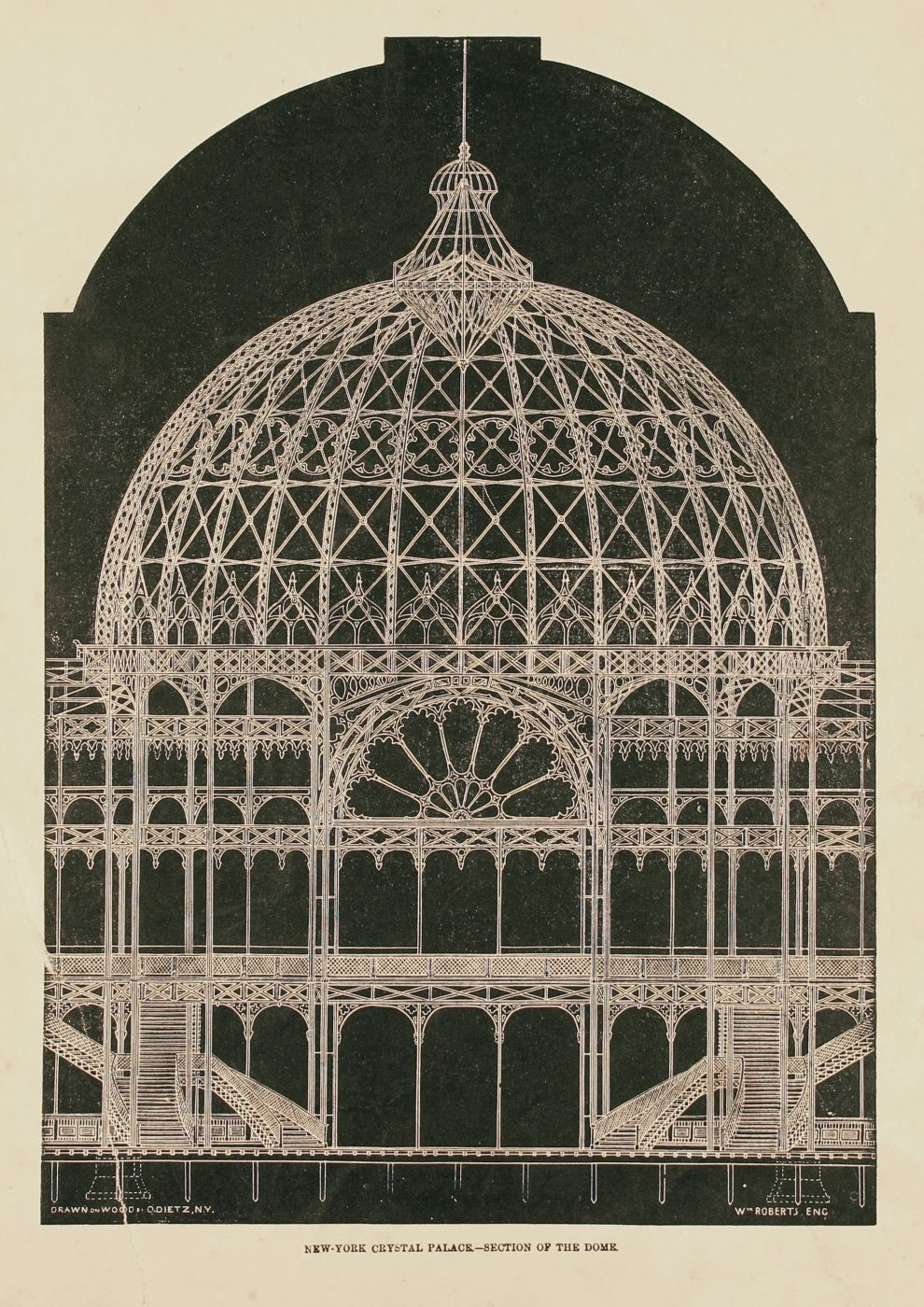

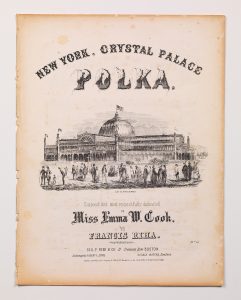

In formulating the plan for the building of the Crystal Palace, a stipulation was put in place by the Board of Aldermen of New York City that the building would be modeled after British architect Joseph Paxton’s construction in Hyde Park and that the materials—cast iron and glass—be the same as well.3 The building itself, designed by the architectural team of the Danish Georg Carstensen and the New York–based Charles Gildemeister as “a tribute to American industry and ingenuity,”4 was reproduced and disseminated through a myriad of objects emblazoned with its image. These souvenirs served to fix the representative image of the building in the minds of consumers and viewers. For nineteenth-century consumers, owning a piece of memorabilia related to the Crystal Palace and displaying it prominently either in one’s home or on one’s person was a novel phenomenon that had at its core a desire for self-expression on the part of the individual as well as the country at large.5

In the twentieth-century theoretical discourse around the object as a repository of cultural memory, souvenirs serve to “envelop the present within the past”;6 at the same time, they are symbolic markers that directly allude to a collective understanding of a particular sight (and in this case, a particular site).7 Souvenirs that feature the image of the Crystal Palace take decidedly vernacular and highly conventional forms, allowing the image to be both present and prominent in their users’ daily lives. The circumstances in which these souvenirs were obtained are generally omitted from the historical record; thus, using largely anonymous objects to recover the lost significance of an important event in American consumer culture positions such items as “markers of events whose reality has escaped us.”8 That is to say, the value of the souvenir, which is entirely specific to the commemorated event as an encapsulation of the “secondhand experience of its possessor [or] owner,”9 can be uncovered through its material relationship to the original event. The materiality of these souvenirs, then, must be examined within their historic context to understand the ways in which they functioned as representations of the New York Crystal Palace in the mid-nineteenth century.

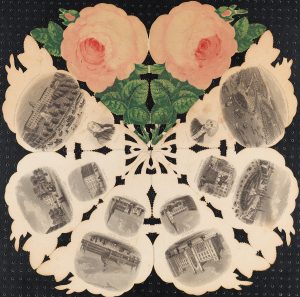

At the time of its construction, the Crystal Palace was the largest structure in the country, with 173,000 square feet of exhibition space occupying that stretch of Sixth Avenue from Fortieth to Forty-Second Street.10 A folded paper souvenir (fig. 1) depicts the Crystal Palace alongside other noteworthy New York City buildings. Rather than focusing on the Crystal Palace as a monolithic entity, this souvenir aligns the building with other significant monuments to American architectural, commercial, and economic achievements, among them the United States Custom House, City Hall, P. T. Barnum’s American Museum, Trinity Church, and the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art.

Fig. 1 Folded souvenir with views of New York buildings, 1857. Printed paper. Museum of the City of New York. 62.46.

Fig. 1 Reverse: Folded souvenir with views of New York buildings, 1857. Printed paper. Museum of the City of New York. 62.46.

“The Souvenir Rose,” as it was known, was a popular item for tourists produced throughout the second half of the nineteenth century by the C. Adler printing establishment of Hamburg, Germany and distributed by the British publisher Joseph, Myers & Company.11 Along with the New York Rose, such souvenirs were produced for Paris, London, Oxford, and Berlin; several other extant Souvenir Roses are accompanied by envelopes whose decorative programs echo the emblems of the particular city depicted, providing evidence that these objects may have been intended for further distribution by their purchasers. A contemporary British advertisement lists the price of these roses at one shilling and describes their format as follows:

This beautiful ornament represents on the exterior a splendid full-blown rose with its graceful form and incomparable tints. At first sight, the flower seems to be a flat piece of thick cardboard, but by carefully introducing the nail between the folds of the paper, it will be found capable of being opened again and again, until it attains somewhat the form of a circle, which is covered on every side with beautifully executed steel engravings of various edifices and other objects of general interest. . . . These pretty ornaments serve as excellent souvenirs of the remarkable places which they represent, and form at the same time very suitable and pleasing presents for tourists and other to carry back to their friends at home.12

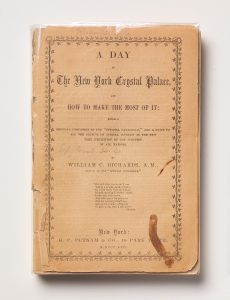

Optical souvenirs, such as miniature peepshows and three-dimensional perspective landscape views, were particularly well suited to the visual representation of the city as spectacle and were prevalent throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.13 The purpose of the paper souvenir was twofold: it replicated the act of looking while presenting a version of the city in microcosm. While the Souvenir Rose lacks the multidimensionality of the peepshow, it nonetheless functions as a “highlight reel” of the leading attractions for a tourist to experience in Manhattan and further illustrates “how the ephemeral souvenir existed in a continual discourse with the monumental.”14 These kinds of “omniscient perspectives” were especially popular in nineteenth-century souvenirs, particularly in representations of world’s fairs.15 For the possessor of this kind of souvenir object, then, “seeing” the city was mediated through the object itself as a surrogate—miniaturized and condensed—for actual visual experience.

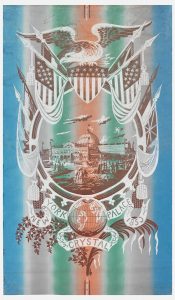

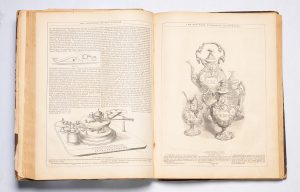

In many ways, the New York Crystal Palace was an American answer to the British exhibition; that inspiration is embodied in a handkerchief adorned with a depiction of the New York Crystal Palace (fig. 2). It is not known whether this handkerchief was printed on site as a memento of a public presentation as at the London Crystal Palace, in which a demonstration of plate printing technologies allowed visitors to observe the production of a scarf bearing the image of the Crystal Palace, which they could then take home as a keepsake.16 The developing industrial machineries of sewing and printing were certainly displayed at the Crystal Palace. In the categories of textile manufacture and the production of “mixed fabrics, shawls, and vestings,” the New York–based French importers, Bertrand Frères, were awarded a bronze medal for their display of lithographic printed linen handkerchiefs, while the Dutch firm of J. Shellers & Son were commended for their “printed cotton handkerchiefs, for cheapness.”17 Like the folded paper souvenir, the printed handkerchief is a visual manifestation of the building as signifier. The handkerchief was a ubiquitous accessory for both men and women; souvenir handkerchiefs came to prominence in the seventeenth century and often depicted city landscapes, unusual events, or deceased persons.18 Their relatively small size and portability made them ideal commemorative objects, and by the nineteenth century, commemorative handkerchiefs enjoyed a position as one of the most common formats for a souvenir.19 The example shown in figure 2 is fairly simple in both design and production; its design was taken from a contemporary engraving of the Crystal Palace and the use of cotton rather than silk made it available to a wider consumer audience.

Fig. 2 New York Crystal Palace handkerchief, ca. 1854. Copperplate printed cotton kerchief with an image of the New York Crystal Palace; printed in black ink on a white ground; yellow border with blue dots. New-York Historical Society, Gift of Miss Susan Smedley (1951.83).

Similar images of the Crystal Palace were also incorporated into a spate of objects intended for domestic use and decor, including a sewing box with an image of the building in mother-of-pearl inlay on its lid, a wall clock with a metal etching of the Crystal Palace in its lower panel, and a silver-toned metal plaque engraving of the building in a simple carved wood frame.20 While these objects lack a traceable provenance, they each indicate the cultural and historical importance accorded to the Crystal Palace. That these are by no means prestigious objects in and of themselves underscores the widespread appeal of the exhibition. The representative image, replicated and disseminated through common objects, further served to position the Crystal Palace as an emblem of American technological, industrial, artistic, and economic progress.

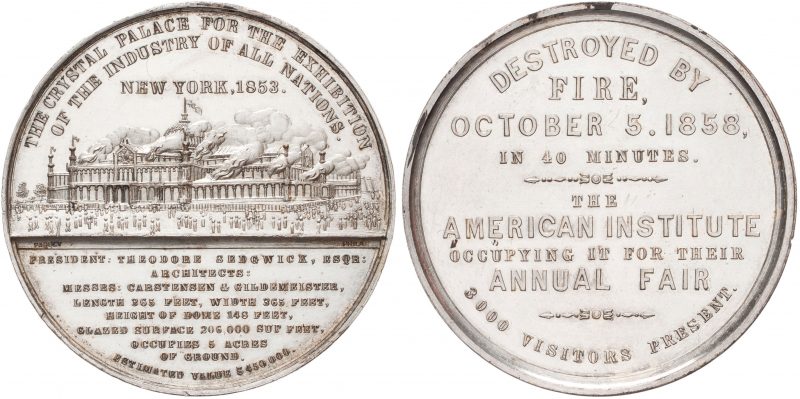

Fig. 3 Anthony C. Paquet. Medal, 1858. Obverse: the crystal palace for the exhibition/of the industry of all nations. / new york, 1853. | president: theodore sedgwick, esqr: / architects: / messrs: carstensen and gildemeister, / length 365 feet, width 365 feet / height of dome 148 feet, / glazed surface 206,000 sup feet, / occupies 5 acres/of ground. / estimated value $450,000. Reverse: destroyed by / fire / october 5. 1858, / in 40 minutes. | the /american institute / occupying it for their / annual fair | 3000 visitors present.

White metal. Courtesy of the American Numismatic Society, 0000.999.8214.

Fig. 4 Wynkoop, Hallenbeck & Thomas. Crystal Palace Relics!, 1858. Wood engraving. Museum of the City of New York, 39.323.

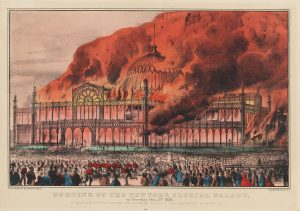

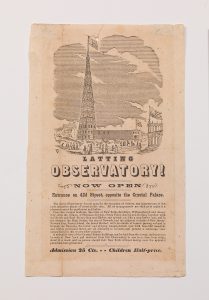

On October 5, 1858, the Crystal Palace was destroyed by fire, a conflagration memorialized by a contemporary white-metal medal (fig. 3). In its aftermath, the building lived on through government-sanctioned sales and auctions of its “relics,” as described in a broadsheet from that same year (fig. 4). Though the building’s monumentality and purported indestructibility were undermined, its symbolism took on a new form through the salvaged pieces of fused glass and iron sold as curiosities (fig. 5), “all that remain[ed] of the finest building ever erected in America.”21 The New York Times echoed that sentiment with a short notice of the auction of approximately 1,800 tons of wrought and cast iron that comprised the building’s remnants, to be held on November 16, 185822. The notice concludes with “sic transit,” a shortened invocation of the Latin phrase sic transit gloria mundi (thus passes the glory of the world), one that succinctly encapsulates the ephemeral spectacle that was the New York Crystal Palace.

Fig. 5 Piece of fused glass, salvaged from the New York Crystal Palace, 1858. Glass fragment. Museum of the City of New York, 36.407.

“The Crystal Palace,” New York Times (May 19, 1853), 1.

“The Crystal Palace,” New York Times (March 10, 1853), 1.

Ivan D. Steen, “America’s First World’s Fair,” New York Historical Society Quarterly 47 (1963), 258.

Charles Hirschfeld, “America on Exhibition: The New York Crystal Palace,” American Quarterly 9, no. 2 (1957): 107.

Christine Ballengee-Morris, “Tourist Souvenirs,” Visual Arts Research 28, no. 2. (2002): 109.

Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984), 151.

Following Dean MacCannell’s description of the marker as symbol in the context of tourism. See Dean MacCannell, The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 131–33.

Stewart, On Longing, 135.

Ibid.

“New York Crystal Palace for the Exhibition of Industrial Products,” Scientific American 8, no. 6 (October 23, 1852), 41.

Sam Ross, “Secret Lives of Objects: Souvenir Roses,” Leeds Museums & Galleries, http://secretlivesofobjects.blogspot.com/2011/11/souvenir-roses.html.

“The Souvenir Rose [advertisement],” James Robinson Planché, Oberon: An Opera in Four Acts (London: Hammond, 1860).

Amy F. Ogata, “Viewing Souvenirs: Peepshows and the International Expositions,” Journal of Design History 15, no. 2 (2002): 70.

Ibid., 74.

Ibid.

See also catalogue record for “Crystal Palace [handkerchief]: Printed in the Machinery Department,” Yale Center for British Art, http://orbexpress.library.yale.edu/vwebv/holdingsInfo?bibId=11119978.

Association for the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, Official Awards of Juries (New York: Bryant, 1853): 40, 45.

Valerie Cumming, C. W. Cunnington, and P. E. Cunnington, The Dictionary of Fashion History (Oxford: Berg, 2010): 99–100.

Dawn Hoskin, “Considerations on a Handkerchief,” Victoria and Albert Museum, http://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/creating-new-europe-1600-1800-galleries/considerations-handkerchief.

The objects can be found at the Museum of the City of New York.

Text of Wynkoop, Hallenbeck & Thomas, “Crystal Palace Relics!” (1858).

“City Intelligence,” New York Times (November 15, 1858): 5.