From Palace to Parlor: Exhibition Display, Consumerism, and Cultivation of Taste at the New York Crystal Palace

Margaret Frick

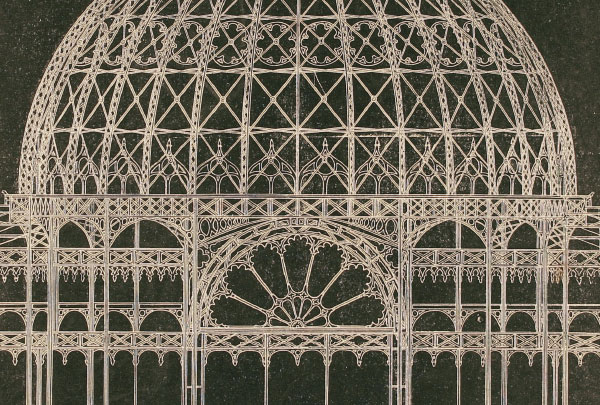

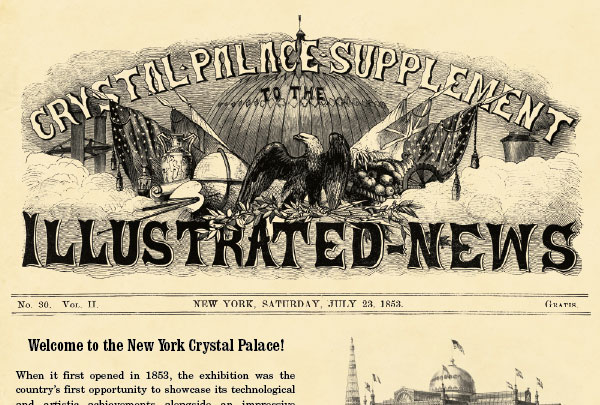

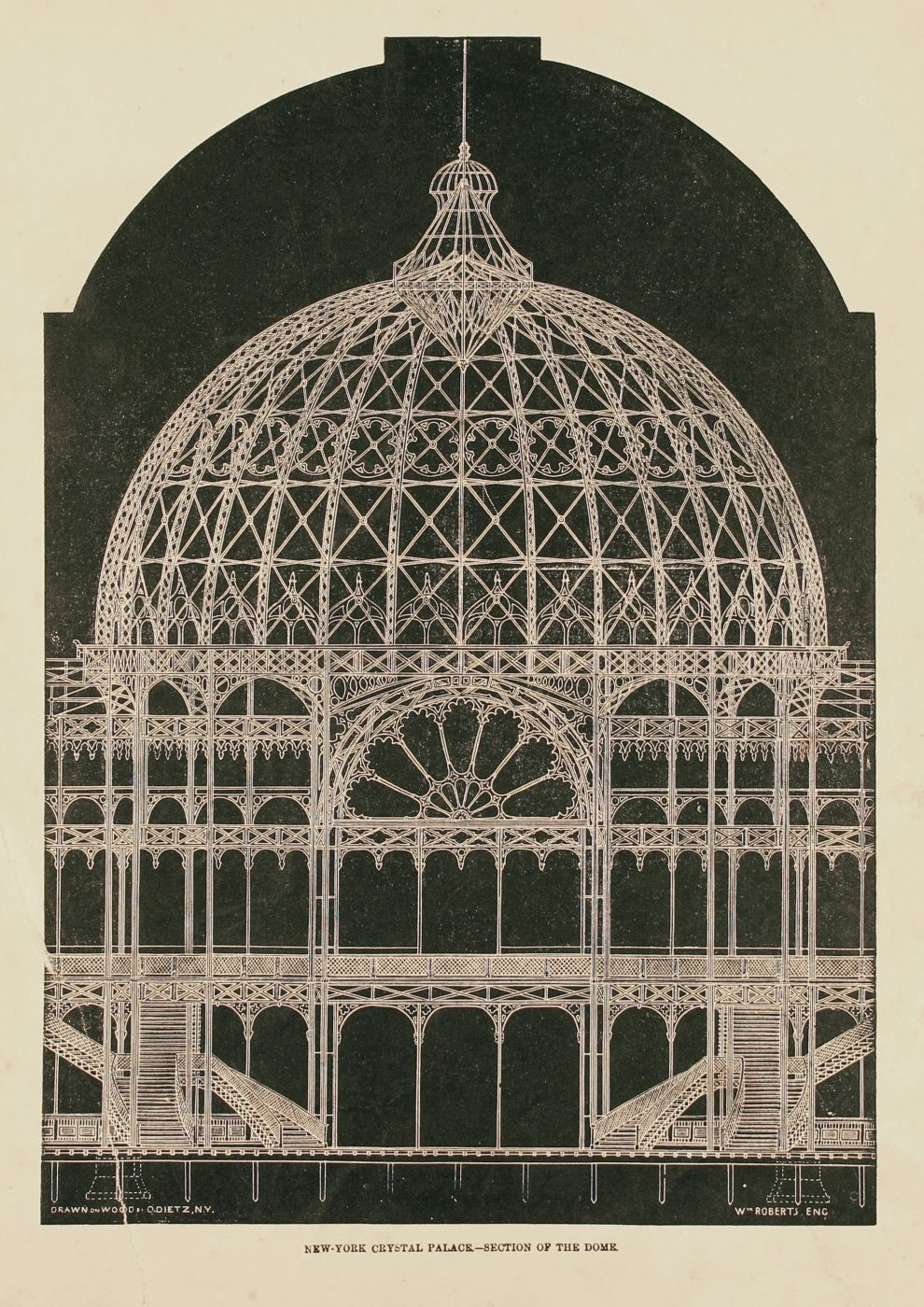

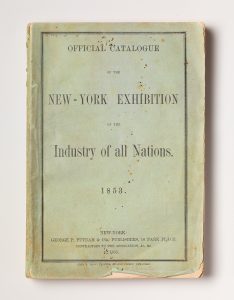

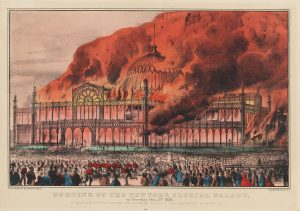

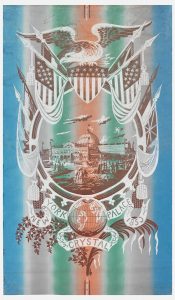

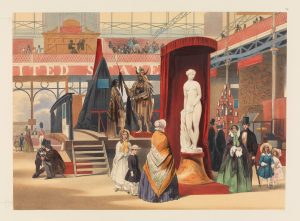

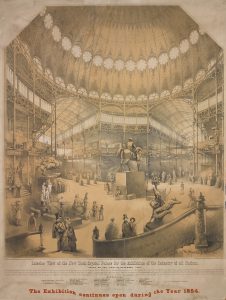

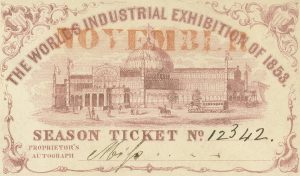

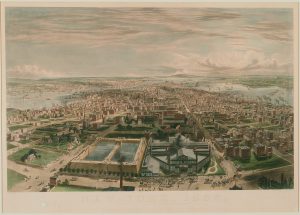

The Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations opened in 1853 at Forty-Second Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues. Although the Crystal Palace was a demonstration of the United States’ ability to compete with European countries, it was also a display of commodities that inspired consumer desire and educated visitors on current styles. Charles Parsons’s lithograph, An Interior View of the Crystal Palace (1853), reveals the “aura of excitement, fun and pleasure, which stimulated the senses, especially the visual one” (fig. 1)1. The variety of goods made available to the public, combined with the splendor of the displays, created an unmatched spectacle for many visitors. This exhibition was a watershed moment for the United States, and it provided manufacturers and retailers an opportunity not only to display their goods to the general public but also to incorporate the Crystal Palace into their advertisements in newspapers and broadsides across the country.

Fig. 1 Charles Parsons. An Interior View of the New York Crystal Palace, 1853. Color lithograph, printed by Endicott & Company, published by George S. Appleton, New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Edward W. C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps and Pictures, Bequest of Edward W. C. Arnold, 1954 (54.90.1047). Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

Although the name of the structure evoked the London Crystal Palace of 1851, the New York exhibition was understood to be a demonstration of the United States’ ability to compete with European industrial innovation and artistic achievement while serving to elevate its citizens’ taste. Contemporary magazines, such as the 1853 Illustrated Magazine of Art, assert the educational experience to be had at the Crystal Palace. An article in Prairie Farmer argues that the exhibition was “no humbug, but [was] a school of wealth and luxury—of taste and refinement—rather than hard-handed utility.”2 The educational underpinnings of the exhibition were particularly aimed at the rising middle class, a group that demonstrated its success through a display of good taste in both clothing and domestic furnishings.

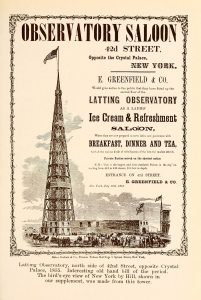

The stores along New York’s famous Broadway, which led visitors to the Crystal Palace, attracted clients with ornate displays and a wide variety of goods. Through advertisements, these businesses sought to maintain their success. With the exhibition, a new opportunity emerged to directly associate one’s business with the Crystal Palace.3 Whether a company had its wares on display, medaled in its class, gathered inspiration for its stores, or participated in the 1854 auction, the aura of prestige surrounding the Crystal Palace was extended to the commercial market.4

Outward appearance was a reflection of personal character and social standing in the middle of the nineteenth century. The industrially produced textiles and clothing were displayed at the Crystal Palace and listed in the exhibition guidebooks.5 Within four broader classifications, section 3 included products manufactured from organic materials, with seven classes of goods specifically related to textiles and fashion.6 One particular display of fashion is chronicled in Godey’s Lady’s Book (October 1853). Mr. G. Brodie, a dry goods merchant, presented “The Regina,” a ladies mantle, or shawl, at the exhibition (fig. 2). It is described as follows:

The ornate grandeur of the Chinese embroideries, worked with exquisite taste upon fabrics of the most sumptuous character, together with the dignified aspect of the style, fully establishes this as the queen of mantles. In order that perfect satisfaction may be afforded to our fair friends, we are gratified to present them with a back view of the “Regina,” upon which the same embroidery as that of the “imperial” is exquisitely wrought in white upon a ground to the heaviest taffeta. It is designed for the opera.7

The allure of luxury and class distinction permeates this advertisement. Global trade brought new goods and imaginative new decorative schemes to Western markets. This cultural interaction produced a market for fantastical or exotic ornamentation, which was applied to interior decoration and clothing. The mention of the opera implies that the wearer is part of a growing leisure class. Clothing was among “the most visible and status-relevant types of consumer goods.”8

Fig. 2 William Roberts after Lewis Towson Voiget. G. Brodie’s advertisement for the “Regina.” Godey’s Lady’s Book, October 1853. Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Fashion accessories were also widely advertised in the New York City newspapers. Mrs. William Simmons, a milliner on Broadway, appeals to both returning “customers and strangers visiting the city” by citing her distinction as the only medalist for “split straw goods.”9 Charles Cook, a fur manufacturer and skin importer, boasts of the production of fur “duplicates of all the shapes in the Exhibition.”10 The wording employed in this advertisement suggests that the displays at the Crystal Palace created a demand for products and that expositions visitors would have visited local suppliers to satisfy their desires.

The larger pieces of furniture on display at the Crystal Palace, such as Julius Dessoir’s Louis XIV Revival suite and Nunns & Clark’s square piano, represent the finest examples of production (fig. 3). They also present highly aspirational examples of the furnishings for the parlor. The piano, manufactured by Robert Nunns and John Clark, is an ornate rosewood instrument, embellished with carved bouquets on the legs and inlaid mother-of-pearl, tortoiseshell, and abalone on the lid. This piece was designed to improve the status of both men, who were British piano makers working in New York. They had displayed another piano, equally as ornate, in the London exhibition in 1851.11 Other makers displayed their instruments at the Crystal Palace, including the Hazleton Brothers, who also exhibited a rosewood piano.12 It is possible that the Nunns & Clark piano was available at the Crystal Palace auction and purchased by a wealthy individual; however, the wide range of options that manufacturers offered, including instruments with simpler, less costly decoration, and installment plans, which also allowed the middle-class to obtain a piano for their homes.

Fig. 3 Robert Nunns and John Clark. Square piano, 1853. Rosewood. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of George Lowther, 1906 (06.1312). Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

During the nineteenth century, the development of new technologies increased the production of consumer goods, allowing producers to make more commodities at a lower cost.13 The elite no longer held a monopoly on luxury objects. As middle-class income rose, a greater number of individuals could purchase a piano for their own homes. Based on advertisements in the New York Times Daily, pianos were popular items, and a variety of both brand new and secondhand instruments were available. The Crystal Palace became a selling point for makers, with headlines such as “Crystal Palace Premium Piano Fortes” from T. H. Chambers, and the longer advertisement by Hazleton & Brothers: “Crystal Palace First Premium Piano Fortes—Hazleton & Brothers offer at their manufactory and warerooms, . . . in plain or ornamented cases.”14 The exhibition certainly created an interest in consumer goods, and makers shaped their inventories to appeal to a variety of buyer needs.

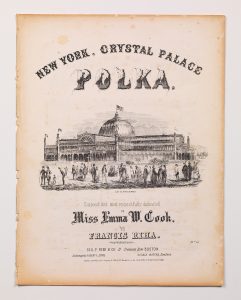

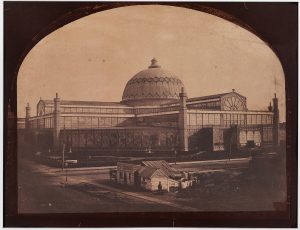

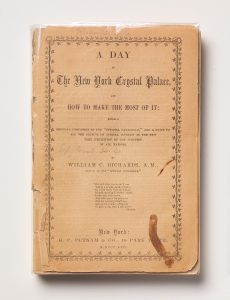

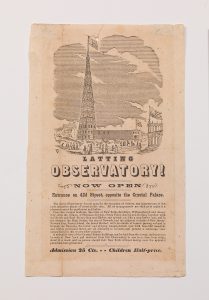

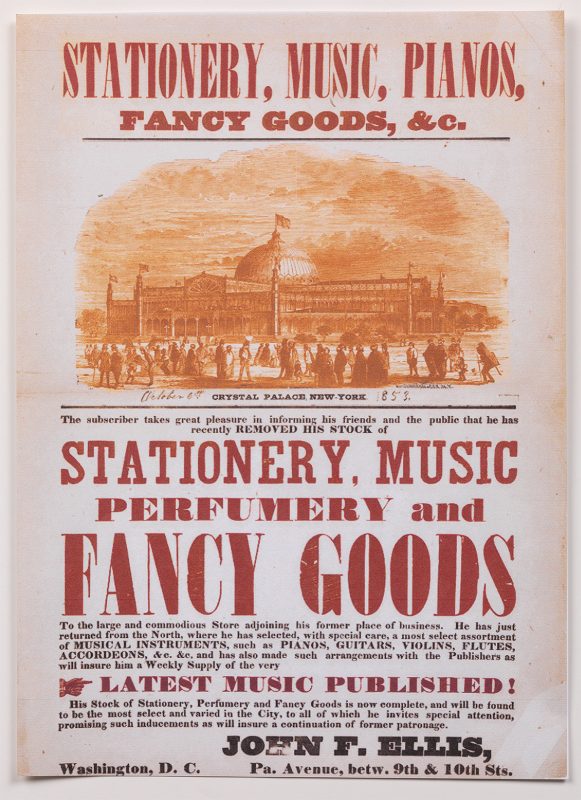

The very image of the Crystal Palace became an icon of conspicuous consumption, and it lent status to merchants across the United States who exhibited there. John F. Ellis, a merchant in Washington D.C., incorporated an engraving of the Crystal Palace in an advertisement for “Stationery, Music, Pianos, Fancy Goods &c.” (fig. 4). The exterior view of the exhibition is quite popular, although the arrangement of people outside varies from designer to designer. The prominent placement of the image on the broadside highlights the claim that Ellis has “just returned from the North, where he has selected, with special care, a most selected assortment” of goods.15 The combination of image and text implies that the Crystal Palace is the standard-bearer for current fashions and indicates that there was a market for these trends beyond New York City.

Fig. 4 Stationery, Music, Pianos, Fancy Goods &c. Advertisement for John F. Ellis’s establishment, October 1853. Private Collection.

Indeed, the Crystal Palace’s sphere of influence is demonstrated in contemporaneous newspapers across the United States. Godey’s Lady’s Book was published in Philadelphia, and it circulated widely, appealing to readers’ interest in contemporary events. The Hazleton Brothers advertised in the Weekly Vincennes Gazette, an Indiana newspaper.16 Print culture allowed manufacturers to circulate their wares, accolades, and inspiration in relation to the exhibition. The large number of visitors who traveled to New York to visit the exhibition also carried what they saw far and wide. By its displayed goods, print culture, and word of mouth, the New York Crystal Palace generated an interest in good taste in middle-class individuals in both rural and urban environments around the country.

Robert D. Tamilia, “World’s Fairs and the Department Store 1800s to 1930s,” Charm (2007), 232.

“The American Crystal Palace,” Illustrated Magazine of Art 2, no. 10 (1853), 258; J. A. K., “The New York Crystal Palace,” Prairie Farmer 13, no. 10 (October 1853), 382.

Dell Upton, “Inventing the Metropolis: Civilization and Urbanity in Antebellum New York,” in Art in the Empire City New York, 1825–1861 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 42. Contemporary parallels were also drawn between the exhibition and dry good emporiums such as A. T. Stewart’s Marble Palace. For more, see Kirstin Purtich, “Palaces of Consumption: A. T. Stewart and the Dry Goods Emporium,” in Visualizing 19th-Century New York (2014), 3–4.

After the exhibition closed on November 1, 1854, many of the remaining display goods were auctioned.

Official Catalogue for the New York Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, 1853 (New York: Putnam, 1853), https://archive.org/details/cu31924031227105.

These classes include (11–14) four types of “Manufactures”: cotton, wool, silk, flax and hemp; (15) “Mixed Fabrics, Shawls, Vesting, &c.”; (16) “Dyed and Printed Fabrics; Tapestry, including Carpets and Floor Cloths, Lace, Embroidery, Trimmings, and Fancy Needlework”; and (20) “Wearing Apparel.” Official Catalogue, 19.

G. Brodie, “The Regina,” Godey’s Lady’s Book (October 1853), 290.

Joanna Banham, Sally MacDonald, and Julia Porter, “Victorian Values,” in Victorian Interior Design (New York: Crescent, 1991), 30; Marilyn Ferris Mortz, introduction to Making the American Home: Middle-Class Women and Domestic Material Culture, 1840–1940 (Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1988), 3; Stuart M. Blumin, “‘Things Are in the Saddle’: Consumption, Urban Space, and the Middle-Class Home,” in The Emergence of the Middle Class: Social Experience in the American City, 1760–1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 141.

“First Premium Millinery,” advertisement in the New York Times Daily (April 25, 1854), 5.

“Furs at the Crystal Palace,” advertisement in the New York Times Daily (December 28, 1853), 6.

Robert Nunns and John Clark, Square Piano (1853), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of George Lowther, 1906, Acquisition Number: 06.1312, http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/503678?ft=piano+crystal+palace&pg=1&rpp=20&pos=2; Martha Novak Clinkscale, Makers of the Piano, vol. 2, 1820–1860 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 267–71.

Clinkscale, Makers of the Piano, 175.

“Classified Advertisements,” New York Times Daily (April 5, 1853), 6; “Classified Advertisements,” New York Times Daily (September 18, 1856), 5; Clinkscale, Makers of the Piano, ix–x; Alfred Dolgy, Pianos and Their Makers (Covina, Calif.: Covina Publishing, 1911), 200.

“Classified Advertisements,” New York Times Daily (April 29, 1854), 6.

“Stationery, Music, Pianos, Fancy Goods &c.,” advertisement broadside (October 1853), private collection.

“Piano Forte Manufacturers,” Weekly Vincennes Gazette (January 7, 1857).