Innovation in the Palace and Revelry on the “Midway”: The Food and Drink of the New York Crystal Palace

Elizabeth Muir

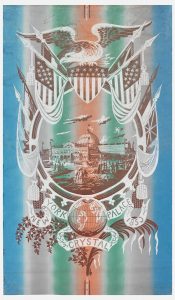

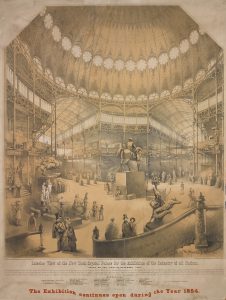

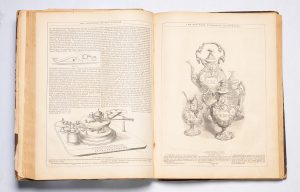

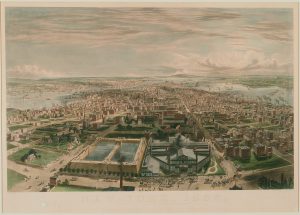

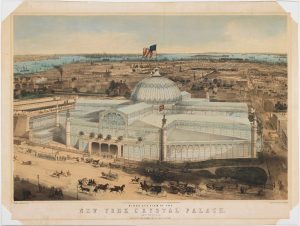

At the 1853 New York Crystal Palace, the exhibit category of “Substances Employed as Food” displayed American ingenuity in food preservation and was closely connected to westward expansion of America. As settlers traveled to settle Oregon and Utah or to join the California gold rush, they needed food that would stay fresh throughout long journeys by covered wagon, horseback, and by sea. Contemporary texts lauded the products on display at the Crystal Palace for the ways in which they would improve these types of travel. In an article on Charles Alden’s coffee in “Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room,” the use of Alden’s distilled coffee extract and preserved milk was praised for its nourishment and value to sea travelers. Figure 1 represents a display of Alden’s wares and notably includes a nationalistic eagle, perched atop a globe, indicating the importance of the United States’ increasing territorial expansion for Alden’s business. In 1853 Alden gave six cases of preserved foods to explorer John C. Frémont, who was set to embark on an expedition to find a viable route for a railroad to California, along with the Jewish American artist Solomon Nunes Carvalho, who created drawings and kept a journal of the journey. Nunes Carvalho wrote about how preserved foods helped to sustain the men when horse and porcupine meat were the only fresh foods available.1 Before the construction of a railway line, the only way to get to California was a roughly six month’s journey by covered wagon or by ship around the tip of South America.

Fig. 1 “Charles Alden’s Coffee Contribution to the Crystal Palace.” From Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room, January 28, 1854.

Also in 1853, the Crystal Palace exhibitors Solomon Wardell and Joseph M. Pease sold alimentary preserves, dry goods, and pickles. An intact Wardell’s bottle (along with fragments of the same type of bottle) were found in an archeological excavation of the waterfront store William C. Hoff’s Emporium in San Francisco, which burnt down in 1851.2 Transported by ship, most of the bottles and dry goods of this frontier outpost came from New England or the New York area.3 With the gold rush still booming, it is possible that other preserved foods on exhibit at the Crystal Palace would have traveled to California. The Crystal Palace was a good venue for innovators to show off methods of preserving food, as many visitors saw and experienced these new foodstuffs.

New York Crystal Palace Brandy Smash, 1853

1/2 oz. Simple Syrup2 oz. Brandy4 Sprigs of Fresh Mint1/2 oz. Lemon Juice1/2 oz. Water

- Add the brandy and simple syrup to a shaker filled with ice. Shake vigorously, then add the mint and gently shake for 10 seconds.

- Strain the contents of the shaker into a tumbler filled with ice and garnish with mint.

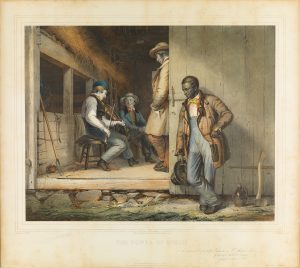

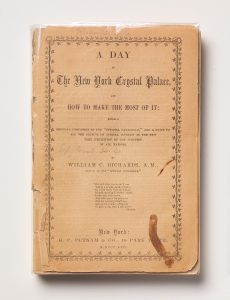

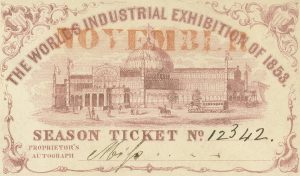

Not everyone traveled to the Crystal Palace at Forty-Second Street for edification, even if that was the primary goal of the exposition’s organizers. Many visitors made the trip uptown solely to drink at one of the hundreds of “groggeries” that materialized on the midway outside of the Crystal Palace.4 For the visitor, there were a wide variety of drinking establishments to choose from, including a railroad-themed bar with rides, beer gardens frequented by German immigrants, and canvas tents that served liquor at three cents a glass. One of the most common drinks was the “Brandy Smash,” a mixture of brandy, sugar, and lime shaken in a cocktail shaker. A newspaper writer who visited the Crystal Palace midway observed that a “number of people who dr[a]nk themselves out of existence” in New York did so through these smashers. With distaste, the author goes on to describe the crowds of people outside of the Crystal Palace, which included “New York rowdies,” Germans, Frenchmen, Irishmen, and very few “decent Americans” (a reference to the paucity of middle- and upper-class, American-born, white men and women).5 While working-class men and women freely mixed on the midway, eating and drinking inside the Palace and the Latting Observatory was gender segregated into men’s and women’s saloons.

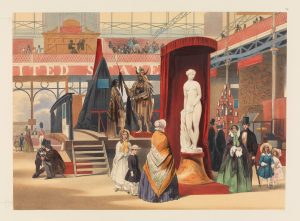

In the nineteenth century, “saloon mania” hit New York. The term “saloon” was used for a range of establishments that that included oyster houses, billiard parlors, and ice cream eateries. “Saloon” may come from a bastardization of the French salon, but the name in the nineteenth century was used to indicate an establishment for eating or amusement. A variety of eateries ranging in price and clientele employed the term, from cheap oyster bars to the finest restaurants. Finer locations were often gender segregated for women to safely dine without the company of men. According to social conventions, middle-class women would not want to be seen inside a location that served alcohol, as it could damage her reputation. As even fine restaurants such as Delmonico’s provided private boxes for paramours and their ladies to dine in secret (fig. 2). Dining out was often portrayed in contemporary texts as a dissipated social activity. Noticing a gap in the market, dining locations began to cater to middle-class women by creating gender-segregated spaces. Within the Crystal Palace, the Ladies Saloon, indicating that this was a space for women to safely dine and eat without the presence of alcohol.

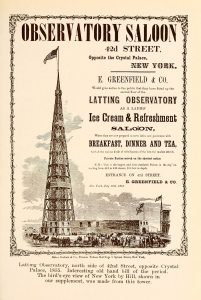

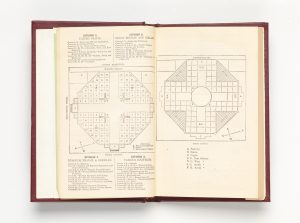

Fig. 2 Henry Collins Brown. “Latting’s Observatory Saloon Advertisement.” From Valentine’s Manual of Old New York (Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Valentine’s Manual, 1919).

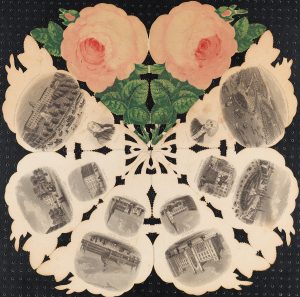

A newspaper advertisement for the refreshment saloons in the Crystal Palace suggests that these rooms, which accommodated two thousand people, were created for a wealthy dining culture that was used to variety and novelty. The menu includes “an extraordinary amount of Refreshments, Oysters, Relishes, Ices, Ice Creams.”6 Because of the high cost of outfitting the rooms with fine furniture and china, the food in the saloons was prohibitively expensive. There were no other options for food, so once you bought your ticket and went through the turnstiles, the only places to eat were these official refreshment rooms.

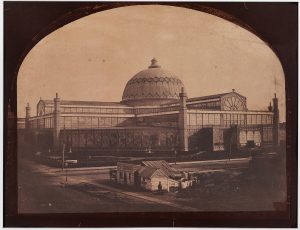

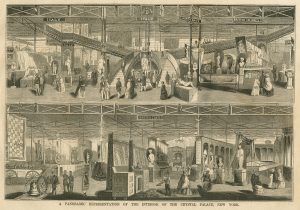

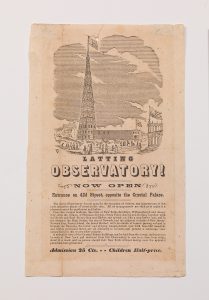

Across the street at the Latting Observatory, there were also gender-segregated spaces for women to dine at the “ice cream and refreshment saloon,” which were publicized in a broadside as having a Ladies’ Refreshment Saloon (fig. 3). Once a treat that only the wealthy could afford, ice cream became ubiquitous in the nineteenth century as a result of lower sugar prices, the rise of commercial ice cream churns, and faster transportation of milk and eggs from rural farms into cities. In place of alcohol, ice cream became a way for women to indulge in a sweet, yet respectable treat. Ice cream was associated with purity because of its sweetness and lightness, and so it became the perfect comestible to express these traits.7 Eventually turning into “parlours,” the ice cream saloons that flourished across New York show how the role of female consumers became more prominent as women increasingly led the crusade against locations that served alcohol.

Fig. 3 “Interior view of a Broadway, New York, refreshment saloon.” From Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, May 15, 1852. Wood engraving.

The food served inside the Crystal Palace tells us about the growing female-centered movement against the public consumption of alcohol, which called for segregated spaces for women to dine apart from men. The Crystal Palace midway, however, offers a very different story about a vibrant working class drinking culture of immigrants and other Americans who drank and danced—with women—in a great variety of establishments. From the temperance lemonade delicately sipped while inside the Crystal Place to the brandy smashes tossed back outside on the midway, the Crystal Palace represented a microcosm of the larger dining cultures of urban New York.

Solomon Nunes Carvalho, Incidents of Travel and Adventure in the Far West: With Col. Frémont’s Last Expedition across the Rocky Mountains: Including Three Months’ Residence in Utah, and a Perilous Trip across the Great American Desert to the Pacific (New York: Derby and Jackson, 1860), 107.

Dennis P. McDougall, “The Bottles of the Hoff Store Site,” in The Hoff Store Site and Gold Rush Merchandise in San Francisco, California, edited by A. G. Pastron and E. M. Hattori (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Braun-Brumfield, 1990), 65.

James P. Delgado, Gold Rush Port: The Maritime Archaeology of San Francisco’s Waterfront (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 147.

“The Crystal Palace on a Sunday,” Albion: A Journal of News, Politics and Literature, June 25, 1853.

Ibid.

“Refreshment Rooms,” New York Daily News, June 13, 1854.

Wendy A. Woloson, Refined Tastes: Sugar, Confectionery, and Consumers in Nineteenth-Century America (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2002), 79.