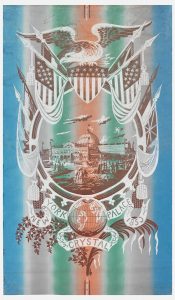

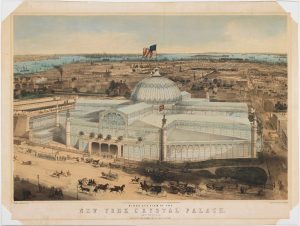

Building the New York Crystal Palace

Sheila Moloney

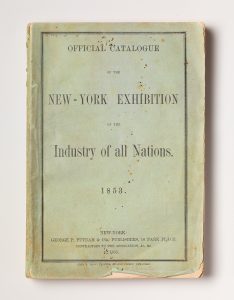

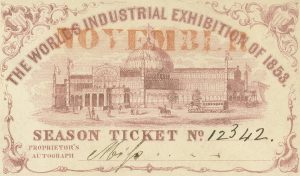

On a spring day in 1851 in the city of London, more than two years before the Crystal Palace exhibition opened in New York, an unprecedented exhibition conceived on a massive scale opened to the public, and in many ways the world would never be the same. A display of arts, inventions, and products of industrial manufacture from countries around the world, the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations was the first international exhibit of the technical achievements and consumer goods of the industrial era. It attracted more than six million visitors by the time it closed six months later and immediately spawned the cultural phenomenon of the world’s fair.

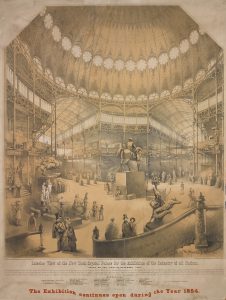

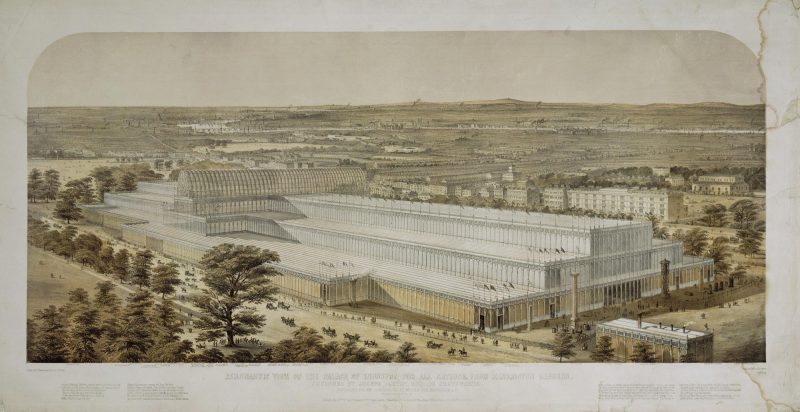

The exceptional nature of the exhibition was underscored by the architecture of the building in which it was housed (fig. 1). The enormous structure was made almost entirely of iron and glass, ancient materials hitherto available only in limited quantities and chiefly for small luxury items. Reconfigured into the new forms of cast iron and plate glass in the crucible of the Industrial Revolution, they were now available in large quantities and became not just the products of industrialization but one of its driving forces. The reflective, transparent, and varied visual properties of the cast iron and glass building provided the exhibit with its popular name, the Crystal Palace. Joseph Paxton, a gardener and designer, provided the plan for the building based on his large greenhouses, including the “Great Stove,” the conservatory he built at Chatsworth to house the exotic plants of the Duke of Devonshire (fig. 2). The Crystal Palace was the largest building in the world, but because it was constructed of modular, prefabricated, and standardized cast iron columns, beams, girders, and trusses and glass panes, it took only seventeen weeks to construct.

Fig. 1 Charles Burton. London Crystal Palace, 1851. Color lithograph. Published by Ackermann. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 19614.

Fig. 2 Joseph Paxton. Greenhouse (“The Great Conservatory”) of 1837 at Chatsworth House, Derbyshire, 1836-40. Photograph ca. 1910s. Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo.

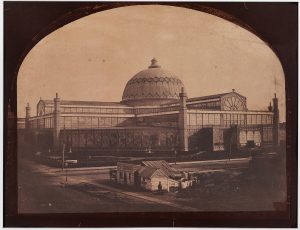

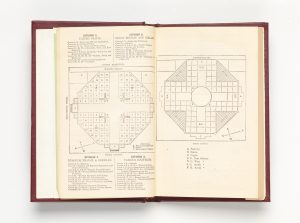

A group of New York City politicians and businessmen soon began planning their own international exhibition and invited proposals for the design of the building in the summer of 1852. Their only stipulation was that the building must be constructed entirely of cast iron and glass. The organizing committee selected the design submitted by Georg Carstensen and Charles Gildemeister, both recent arrivals to New York. Carstensen was from Denmark, where he had created Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, a pleasure garden and amusement park modeled after London’s Vauxhall Gardens, and Gildemeister was from Germany, where he had trained as an architect. One of the paradoxes of the New York Crystal Palace is its reliance on an ancient architectural template while simultaneously using new industrial-era materials.1 Carstensen and Gildemeister based their design on the central symmetry of the square Greek-cross plan, a form of ecclesiastical architecture.

Fig. 3 August Petermann and Karl Gildemeister, designers; August Petermann, lithographer. New York Exhibition Building, 1852. Lithograph. Museum of the City of New York, 31.224.12.

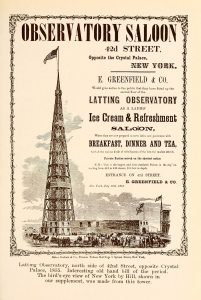

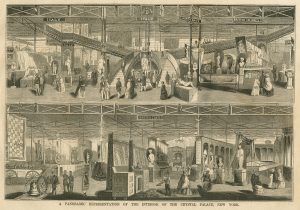

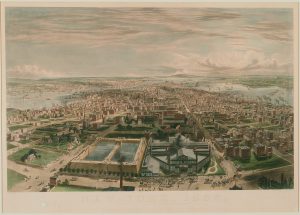

While the London Palace was erected on the extensive landscaped grounds of Hyde Park, the New York Crystal Palace was confined to Reservoir Square, bounded by the city’s rigid grid system to a square block between Fifth and Sixth Avenues and Fortieth and Forty-second Streets, the current location of Bryant Park.2 To maximize the usable space on the small site, the architects added triangular wings to the four corners of the square cross, creating an octagon that filled almost the entire lot.3 The architects faced another design problem in the massive, fortress-like Croton Distributing Reservoir, source of the city’s drinking water, which loomed over Reservoir Square. To compete visually with this immense structure, they surmounted the middle of the cross with an enormous dome, larger and higher than any in the United States. They also solved the problem of the frequently unbearable summer temperatures inside the London Crystal Palace by having the plate glass panels coated with variously colored enamel. This effect, and the ease with which cast iron could be shaped into mass-produced structural elements evocative of Classical, Gothic, and Byzantine forms, allowed for a richly designed interior and exterior that provided visitors with a stunning visual experience. In their description of the building, the architects explained that it was designed “mostly in the Venetian style, the most favorable for lightness and elegance.”4

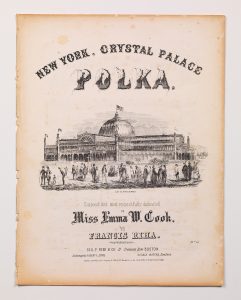

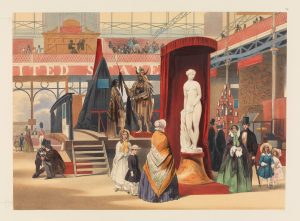

With its lofty, enormous dome and huge interior space, the Crystal Palace was one of the largest buildings that New Yorkers would have experienced, similar in effect to a Gothic cathedral. The aesthetic appeal of the new technology of cast iron is demonstrated in the elegant, slender columns and graceful structural tracery in this interior scene. The visual effect of the iron framework, painted in cream and accented with reds, blues, yellows, and gilt, surmounted by the delicately tinted, tin-sheathed dome banded with horizontal rows of decorative windows, inspired superlatives. Frequent visitor Walt Whitman wrote that it was “certainly unsurpassed anywhere for beauty . . . an original, aesthetic, perfectly proportioned American edifice—one of the few of modern times not beneath old times.”5 One contemporary source gushed, “the rays from a golden sun descend between the latticed ribs into a soft heaven of azure,”6 and another exclaimed, “what a blaze of light and beauty flashes on the dazzled eye! What exquisite proportions in the unique dome! What admirable harmony of coloring. . . . How airy and graceful the delicate tracery of arch and column!”7

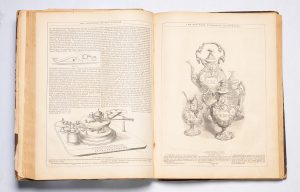

Fig. 4 New York Crystal Palace—Interior View. From Benjamin Silliman and C. R. Goodrich, eds., World of Science, Art, and Industry, Illustrated from Examples in the New-York Exhibition, 1853–54 (New York: Putnam, 1854). Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

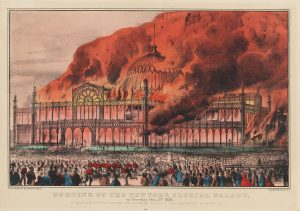

Although the official Crystal Palace exhibition closed in 1854, the building was still being used for other shows when a fire ravaged the entire structure in less than half an hour in October 1858. Although the cast iron and glass construction was presumed to be fireproof, the wooden floors and items on display were not. Ironically, the fire drew thousands of onlookers, and in its demise the Crystal Palace attracted the largest crowds since its opening.8

The brief life of the Crystal Palace provides insight into the massive transformations that took place in the social, cultural, and economic life of New York City in the mid-nineteenth century, as well as into the state of the city’s architecture. The New York Crystal Palace was a symbol of the rapid and enormous growth of commerce and industry in the city and its emerging role as the commercial and cultural capital of the country. It is representative of the constantly changing appearance of the city: old buildings continually disappeared through demolition and fire and newer, often larger ones immediately sprang up in their places. Its location at Forty-Second Street, the northern edge of the inhabited city, marks the relentless expansion northward of buildings and people as the city’s population exploded beyond its original center at the southern tip of Manhattan.

In the annals of architecture in New York City, and in that of world’s fairs, the Crystal Palace was more of a novelty and an experiment with newly available materials than a structure with lasting influence. Architectural historian Sigfried Giedion dismissed the building as having “no historical importance.”9 The use of cast iron was becoming more widespread in the mid-nineteenth century, particularly in bridges, factories, warehouses, and large department stores. But its pairing with plate glass in a uniquely integrated architectural form, as in the London and New York Crystal Palace buildings, has subsequently been confined mainly to train stations and shopping arcades in urban areas and to greenhouses in rural areas and parks. World’s fairs had largely abandoned the cast iron and glass exhibition halls by the end of the 1850s. The iron and glass aesthetic in civic architecture had limited appeal. New York was a city of brick, stone, and, increasingly in the nineteenth century, marble, and it was these materials, and their association with tradition and permanence, that continued to be used in the majority of public and private building. In an 1856 edition of the Crayon, a respected New York art magazine, the editors discussed the future of iron and glass architecture: “After the New York Crystal Palace experiment, we do not think there is much probability of the erection of similar structures in other parts of the United States. Our Crystal Palace was not a successful enterprise. If it had been, there would have been no end to iron and glass structures with us. . . . Public buildings require stone and bricks. These are the true materials for the architect to use. Iron and glass must be secondary and subservient.”10 While the editors of the Crayon seem prescient in their assessment of the influence of the building on subsequent cast iron and glass architecture, they could not have foreseen that cast iron itself as a structural material would largely be replaced by steel later in the century, and that plate glass would be available in ever larger dimensions, ushering in a new era of skyscrapers in American cities in the late nineteenth century. Nevertheless, the Crystal Palace represents a momentary expression in glass and iron of the state of commerce and culture in mid-nineteenth century New York City.

The London Crystal Palace was also based on the ancient Roman and Early Christian basilica.

For visitors to the BGC Crystal Palace Focus Gallery Exhibit who want to get a sense of the size of the building and the extent of the changes to the city since 1853, a visit to Bryant Park is highly recommended.

It became apparent during construction that the size of the building would be inadequate to house all the exhibits that the organizers were collecting. Carstensen and Gildemeister were forced to design an additional wing for large machinery, to the detriment of the building’s aesthetic and formal unity.

Georg Carstensen and Charles Gildemeister, New York Crystal Palace: Illustrated Description of the Building (New York: Riker, Thorne, 1854), 49.

Walt Whitman, “Grand Buildings in New York City,” Brooklyn Daily Times, June 17, 1857.

Charles Hirschfeld, “America on Exhibition: The New York Crystal Palace,” American Quarterly 9, no. 2, pt. 1 (Summer 1957), 109.

Hirschfeld, American Quarterly, 115.

Ibid.

Sigfried Giedion, Space, Time, and Architecture (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982), 199.

The Crayon 3, no. 9 (September 1856), 272.