Struggle for the Shady Side of the Omnibus: Public Transit at Mid-Century and the New York Crystal Palace

Lara Schilling

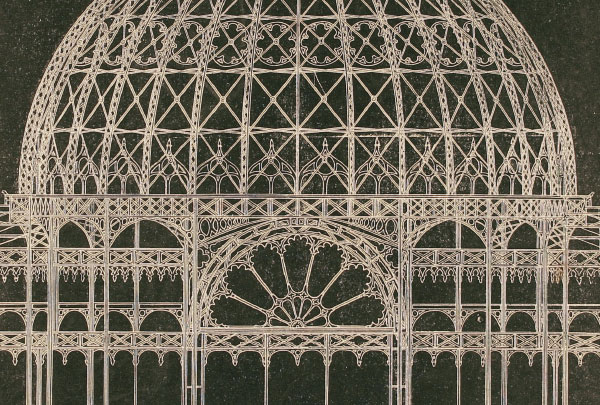

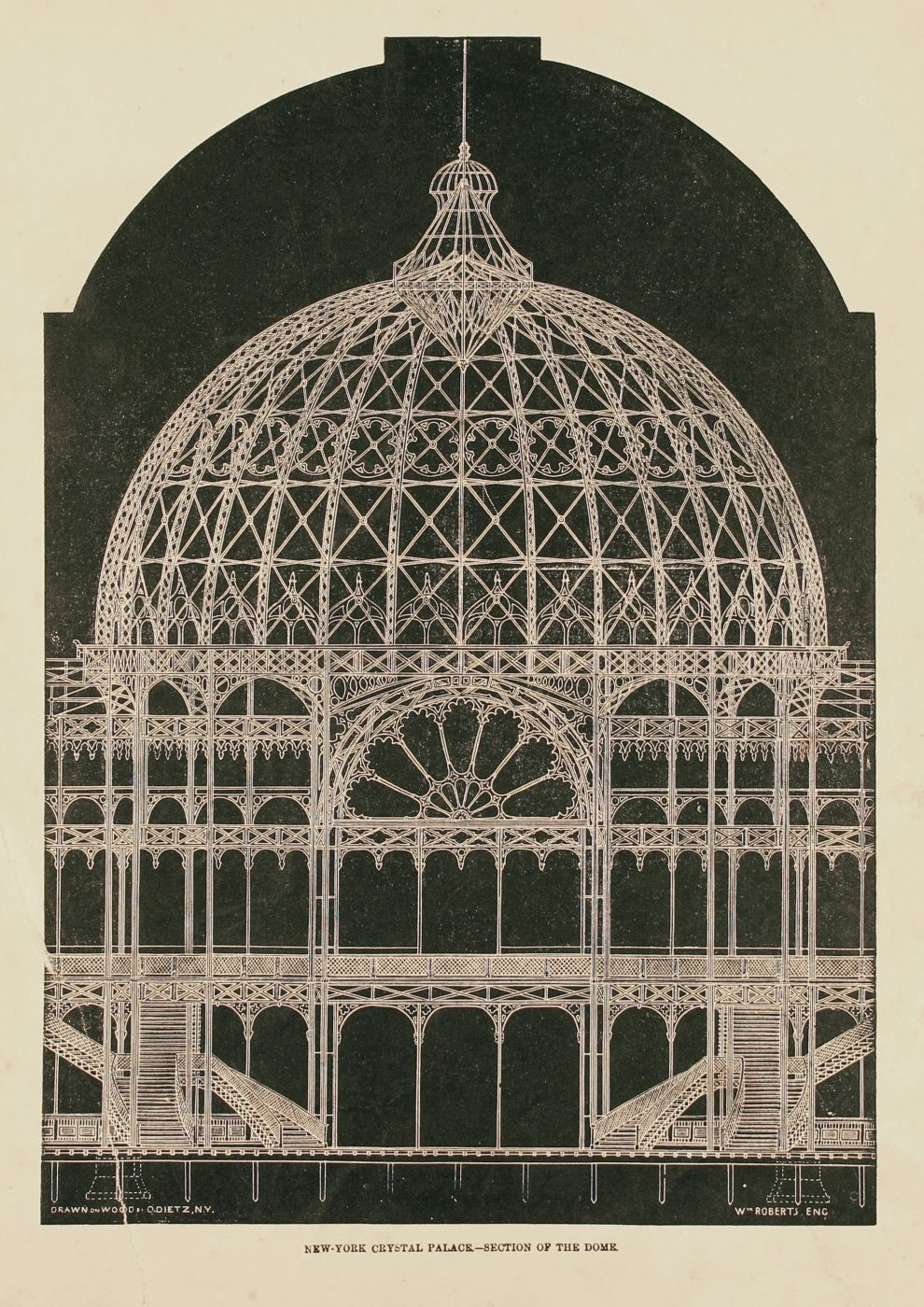

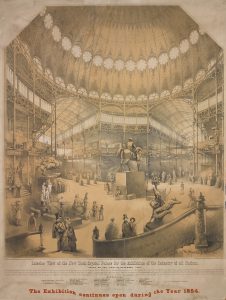

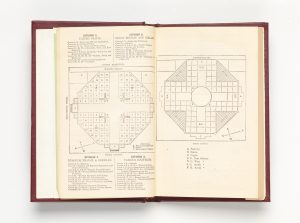

The shape of the ground is unfavorable for architectural purposes; and, aside from the facilities of access afforded by the Avenue railways and numerous lines of stages, there is nothing to recommend this locality, while the solid and imposing strength of the Reservoir presents an inharmonious contrast with that light and graceful structure which we now proceed to describe.

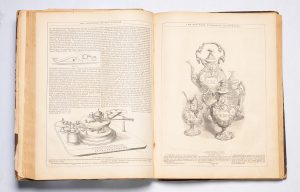

Official Catalogue of the New-York Exhibition of the Industry of all Nations

Around the middle of the nineteenth century, few inhabitants of New York City owned private carriages. While wealthy families often had one or more carriages at their disposal, members of the middle class and working-class New Yorkers traversed the rapidly expanding city using a widening range of semipublic conveyances: hackneys, omnibuses (also called stagecoaches, or “stages,” in the period), and horse-drawn rail cars. Owned by individual entrepreneurs or private companies, early transit lines capitalized on and regulated the movement of New Yorkers and tourists throughout the city. This essay discusses the development of public transit in New York from around 1830 to 1860 and looks at transit’s important role in strengthening and increasing access to the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations held at the New York Crystal Palace in 1853. The essay will also explore the significance of mid-nineteenth-century public transit as a site of social tensions and segregation.

The earliest form of transit-for-hire in New York, hackneys—commonly called “hacks” in period texts—were traditional wooden stagecoaches or carriages that could be hired to transport one individual or small party at a time, much like taxicabs today. In New York, primarily the urban middle class patronized the hackneys, but suburbanites who could not afford to own and maintain a private carriage did so as well. In the early years of the nineteenth century, regularly scheduled, short-distance hacks became increasingly popular, paving the way for the development of the omnibus, which, as the first regularly scheduled street vehicle with a fixed rate and far larger capacity (some could transport up to twenty-eight passengers at a time) offered a significant improvement.1

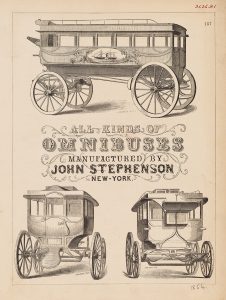

Between 1827 and 1829, Abraham Brower began operating twelve-seater omnibuses, designed and manufactured by John Stephenson, on the streets of New York (fig. 1).2 Brower’s early omnibuses were little more than elongated stagecoaches with a bench on either side of the interior running from the front to the rear, where the entrance was located. Weighing about 2,500 pounds each and pulled by three to four horses at a time, omnibuses purportedly reached no more than five miles per hour.3 Period accounts, however, often suggest otherwise, alternately reveling in and bemoaning the dangerous, breakneck pace of some omnibus lines, which rattled along the streets “at a killing pace,—especially if there be any small children or ‘slow’ pedestrians in the way.”4 Yet despite the dangers, omnibuses had become so popular by 1852 that more than thirty lines operated below Forty-Second Street, with 120,000 passengers using them daily.5

Fig. 1 John William Orr. All Kinds of Omnibuses Manufactured by John Stephenson New-York, ca. 1856. Advertisement. Museum of the City of New York, 31.26.101.

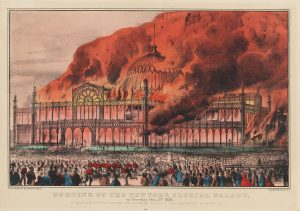

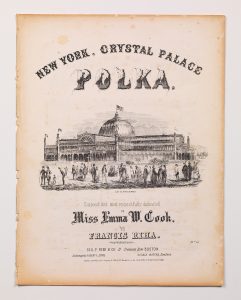

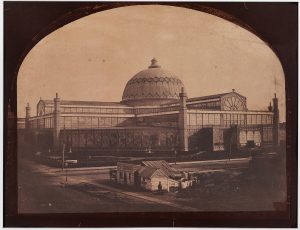

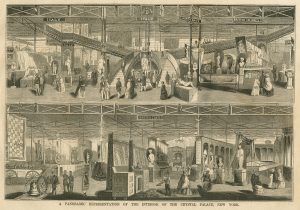

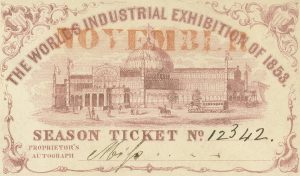

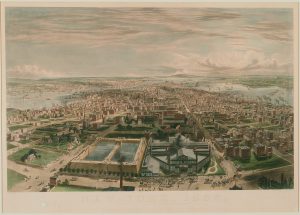

When the Crystal Palace opened its doors to the public in the summer of 1853, “four miles distant from the Battery, and three and a quarter from the City Hall, between the Sixth Avenue and the Croton Distributing Reservoir,” it was part of an extensive network of omnibus lines, many of which identified the Palace as their newest (and often northernmost) destination.6 Exhibition goers could also reach the Crystal Palace by horse-drawn railways, an even newer form of public transit. Unlike omnibuses, which “jolt[ed] you a few streets in . . . rattlety-bang vehicles,” horse cars ran on grooved iron rails that were embedded in the street’s rough, uneven surface, ensuring a smoother ride.7 The first horse-drawn railroad was chartered in 1852 and ran along Sixth Avenue between Chambers and Forty-Second Streets, perhaps in anticipation of the completion of the Palace (fig. 2)8. By the late 1850s, rails had been installed up and down nearly every avenue of the city.9

Fig. 2 Inauguration of the Crystal Palace—Exterior of Sixth Avenue car; Inauguration of the Crystal Palace—Interior of Sixth Avenue car; Inauguration of the Crystal Palace—Rush at the entrance. From Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, 1853. Woodcut. Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Omnibus and railroad companies were quick to capitalize on the Crystal Palace’s northern location, imagining the exhibition hall would herald uptown Manhattan’s becoming a new cultural center, or at the very least, serve as a positive signifier of the city’s commercial and residential expansion to the north. In his year-end report to the Sixth Avenue Railroad’s stockholders in 1852, the company’s president announced: “The gross income of the road must advance with the advancing tide of population to the upper wards of the island. It must be still further increased by the travel to and from the Crystal Palace.”10 One year later, the president reported that the total number of Sixth Avenue Railroad passengers from the previous twelve months exceeded five and a half million; additionally, “the receipts and profits of the road were sensibly increased by the opening of the Crystal Palace.” The railroad’s course up Sixth Avenue meant that it could stop directly parallel to the Crystal Palace’s west-facing entrance—no other Avenue rail line offered such proximity, though the Empire line of the Sixth Avenue Stage (omnibus) also stopped there.11

Entrepreneur John T. Heird also sought to cash in on the nascent uptown transit market. A few weeks shy of the Crystal Palace’s grand opening, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle announced that John T. Heird and Co. was introducing a new line of omnibuses, which would begin at the Roosevelt, Catherine, and Jackson ferries on the East River and wind its way through downtown up to the Crystal Palace.12 The new line also made stops at Dry Dock (far East Village), the Bull’s Head Tavern at Third Avenue and Twenty-Fourth Street, as well as Franconi’s Hippodrome at Madison Square (fig. 3). Heird shrewdly incorporated the Crystal Palace into a network of urban attractions that would have probably appealed to locals, suburbanites, and tourists alike.

Fig. 3 Edward B. Purcell; Frederick J. Piliner, engraver. Exterior View of the Hippodrome, on Madison Square, New York. From Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, June 18, 1853. Art and Picture Collection, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

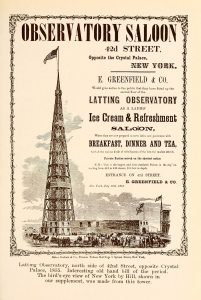

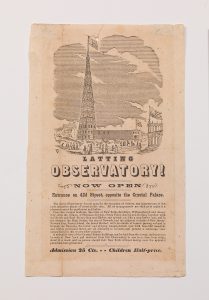

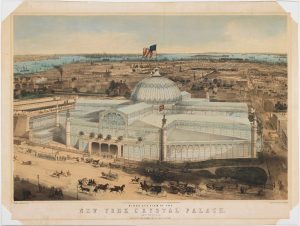

Many other omnibus and rail lines claimed to bring Crystal Palace visitors right up to the magnificent glass building’s doorstep.13 Looking past the excited crowds amassed along Sixth Avenue in the foreground of Capewell & Kimmel’s 1853 engraving of the Crystal Palace (fig. 4), we can spot a twelve-seater omnibus with “Broadway 44th Street” painted on its side (fig. 4a), myriad private carriages and cabs, and a Sixth Avenue horse car. Fanny Palmer’s hand-colored lithograph of the Palace (fig. 5) depicts a similar scene; however, she chose a vantage point on the southwest corner of Sixth Avenue, while Capewell & Kimmel’s image places us closer to the avenue’s northwest corner. In Palmer’s version of the hubbub surrounding the Palace, a Sixth Avenue horse car packed with passengers moves in the direction of the Latting Observatory. To its right, an elaborately painted omnibus featuring a portrait bust heads off in the other direction (fig. 5a, b); it is equally packed with passengers, and its painted side indicates that it will take them as far as Fulton Ferry, if they so wish.14

Fig. 4 William Pate, printer. The New York Crystal Palace and Latting Observatory, 1853. Capewell & Kimmel, publisher. Engraving. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Fig. 4a Detail of omnibus. From The New York Crystal Palace and Latting Observatory, 1853. Capewell & Kimmel, publisher. Engraving. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

While Capewell & Kimmel and Palmer’s prints depict public conveyances that, for the most part, set visitors down “at the very door of that gilded and beautifully-glazed institution,” not all omnibus and rail lines did so.15 A week before the Crystal Palace opened, a journalist for the New York Daily Times implored the Eighth, Fourth, and Third Avenue lines to make stops closer to the Palace. Otherwise, the journalist argued, passengers attempting to reach the Crystal Palace would discover, “on disembarking, instead of the eye-brightening vision of the world-renowned palace . . . a desert of rocks and untamed lots, with goats feeding at random, and the Latting Observatory a weary way off.”16 Popular images of the Crystal Palace typically emphasized the excitement and crowds in the building’s immediate vicinity, creating the impression that the entire region was bustling with activity. The journalist’s dispirited vision of the area around the Crystal Palace is an important reminder that despite the increased fervor to add transit lines north of Forty-Second Street and support the movement of businesses and residents to upper Manhattan, the region would remain largely rural for at least ten more years.17

Fig. 5 Fanny Palmer for N. Currier. New York Crystal Palace, 1853. Hand-colored lithograph. Museum of the City of New York, 29.100.2479.

Fig. 5 (a,b) Details of boxy rail car (a) and fancy omnibus (b). Hand-colored lithograph. Details from Fanny Palmer for N. Currier. New York Crystal Palace, 1853. Hand-colored lithograph. Museum of the City of New York, 29.100.2479.

The construction in New York in the early 1850s of horse drawn railways, which were cheaper to maintain and operate than omnibuses, resulted in a citywide decrease in public transit fares. The horse railroads cost just sixpence per ride, pressuring omnibus companies to lower their rates, which had previously ranged anywhere from one shilling to twelve cents.18 Perhaps the appearance by 1851 of popular lithographs and engravings inside omnibuses represents a strategy employed by some omnibus proprietors to lure more well-to-do, middle-class passengers through added cultural value.19 As described in the Bulletin of the American Art-Union, the artworks’ “chief value in our eyes is the fact that they seem to indicate, that art is beginning to connect itself more closely with the pleasures and occupations of every-day life.”20 Public transit’s ability to concretely manifest a new democratic arena, whereby “the omnibus is regarded as the property of everybody who can pay his sixpence for a ride,” may have simultaneously inspired fear among certain folks and an attendant desire to redraw the wavering boundaries between social classes.21 Indeed, in an 1862 article entitled “City Cabs and Omnibuses,” a writer for the New York Herald declared: “From the disgraceful manner in which the cars are kept and run, all cleanly and respectable people would give the preference to the omnibuses.” The writer not only condemned the inexpensive, widely used horse cars as a system, he also summoned the specter of civility to pressure self-identifying “cleanly and respectable people” into choosing one form of transit over the other as a means of publicly demonstrating their social status.

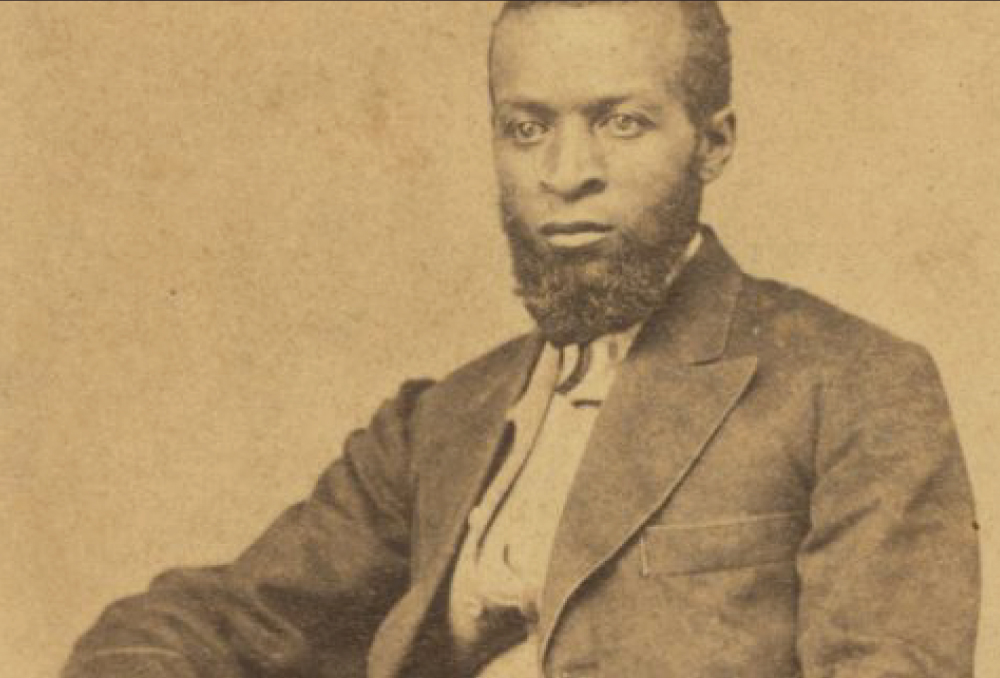

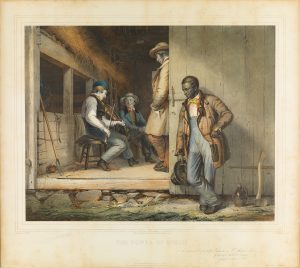

Inflamed social tensions among the city’s ever-growing population in relation to public transit riddle newspaper clippings and sensationalist novels from the 1830s to the 1860s. These sources typically illuminate prejudices against working-class riders, fear of pickpockets and drunken men, distaste for noise and smells, and an overall intensification of social mixing. Less well-documented are incidents that lay bare the long-standing prejudices and racism endured by black New Yorkers. One of few documented cases concerned the Reverend James William Charles Pennington (fig. 6), a prominent orator, writer, and abolitionist who was barred from entering a Sixth Avenue railcar in 1854.22 Pennington’s position and close network of allies helped him bring the matter to court in 1855, although the jury ruled in favor of the railway company when the case finally went to trial two years later.23 Other victims of transit exclusion in the 1850s sought legal recourse as well, including schoolteacher and First Colored American Congregational Church organizer Elizabeth Jennings. Denied access to a Third Avenue streetcar the same year as Pennington, Jennings was awarded $225 and court costs in 1855.24 Out on the street, local police did not always uphold laws mandating equal access and were often accused of aiding racist conductors.25

Fig. 6 Carter Godwin Woodson. J. W. C. Pennington, 1921. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Black New Yorkers increased their protests, using “nonviolent methods to counter segregation on horse cars, railroad cars, and steamboats,” such as “ride-ins” and boycotts, in an era of increased white hostility after the final emancipation in New York of all enslaved African Americans.26 A week after the Crystal Palace opened, Frederick Douglass’ Paper published a letter from a reader that condemned the “shamefully exclusive Sixth Avenue cars” and expressed doubt that blacks would be admitted to the Crystal Palace.27 While the historical record has not yet provided a clear answer as to whether black Americans participated in the exhibition, the racism they experienced in their everyday lives when attempting to use public transit might suggest that black New Yorkers were either not allowed to attend or that perhaps they chose not to.

The study of urban transit in mid-nineteenth-century New York provides rich insights into a period of unprecedented growth, in which regulated, semipublic passenger vehicles increasingly dominated the city streets and brought New Yorkers into closer physical proximity than ever before. At the same time, greater democratization of transit did not extend to all people; rather, it engendered new social stigmas and occasions to discriminate against black Americans. Omnibuses and horse cars were crucial to the Crystal Palace’s early success, enveloping the site within a citywide network that was both reliable and readily adaptable to change. The presence of transit routes uptown played no small role in the region’s commercial and residential development in the ensuing years.

Clay McShane and Joel Tarr, The Horse in the City: Living Machines in the Nineteenth Century (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2007), 55–59.

Ibid., 59. See also Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 460.

Ibid., 60.

See George G. Foster, New York in Slices (New York: W. F. Burgess, 1850), 63. See also “Insolence of Omnibus Drivers,” New York Times, November 17, 1857.

Randall Bartlett, The Crisis of America’s Cities (Armonk, N.Y.: Sharpe, 1998), 71. See also McShane and Tarr, The Horse in the City, 60.

Official Catalogue of the New-York Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations (New York: Putnam, 1853), 7. See also letter to the editor, A Resident, “Bloomingdale,” New York Daily Times, March 22, 1854.

“Cabs,” Frank Leslies Weekly (New York, NY), October 4, 1856.

Ibid., 170–171. See also Citizen, “Sixth-Avenue Railroad,” New York Daily Times, January 20, 1852.

“New York City: Fair of the American Institute—Address by Luther R. Marsh, Esq.,” New York Daily Times, October 26, 1855. See also John H. White Jr., Wet Britches and Muddy Boots: A History of Travel in Victorian America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013), 92–94.

“New-York City: The Sixth-Avenue Railroad,” New York Daily Times, January 11, 1853.

George G. Foster, Fifteen Minutes around New York (New York: DeWitt and Davenport, 1854), 8.

“New Omnibus Line in New York,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 6, 1853. See also “Bull’s Head Tavern: Treating You like Cattle since 1755,” Bowery Boys History, March 20, 2009, http://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2009/03/bulls-head-tavern-hey-astor-wheres-beef.html.

Ivan D. Steen, “America’s First World’s Fair: The Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations at New York’s Crystal Palace, 1853–1854,” New-York Historical Society Quarterly 47 (July 1963), 267–68.

Some omnibus proprietors named each of their coaches after a famous historical personage; perhaps the portrait bust painted on the omnibus in Palmer’s print is of a well-known American figure. See White, Wet Britches and Muddy Boots, 70. See also Burrows and Wallace, Gotham, 460.

“How a Citizen May Get to the Crystal Palace,” New York Daily Times, July 8, 1853.

Ibid.

See Resident, “Bloomingdale.”

McShane and Tarr, The Horse in the City, 63–64.

“Art in the Omnibus,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 3 (June 1, 1851), 48.

Ibid.

“The Power of Caste: Rev. J. W. C. Pennington, the Colored Pastor,” Provincial Freeman (Windsor, Canada West [Ontario]), March 24, 1854.

Ibid. See also “The Rev. Dr. Pennington, a Black Man, Ejected from a Sixth Ave. Car,” Frederick Douglass’ Paper (Rochester, N.Y.), June 8, 1855. See also John Hooker, “Rev. Dr. Pennington,” Frederick Douglass’ Paper, June 26, 1851.

Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626–1863 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 271.

Katharine Greider, “The Schoolteacher on the Streetcar,” New York Times, Nov. 13, 2005. See also Howard Dodson, The Black New Yorkers: The Schomburg Illustrated Chronology (New York: Wiley, 2000), 76–78; Jon H. Hewitt, “The Search for Elizabeth Jennings, Heroine of a Sunday Afternoon in New York City,” New York History 71, no. 4 (1990), 391.

Carla L. Peterson, Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 191–92.

Graham Russell Hodges, Root and Branch: African Americans in New York and East Jersey, 1613–1863 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, c. 1999), 229, 248.

“For Frederick Douglass Paper,” Frederick Douglass’ Paper, July 22, 1853.