Outfitting the Shadows: Policing the 1853 Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in the New York Crystal Palace

Rebecca Sadtler

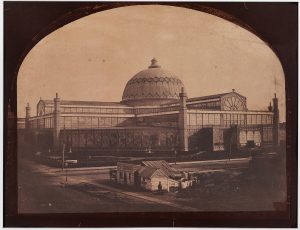

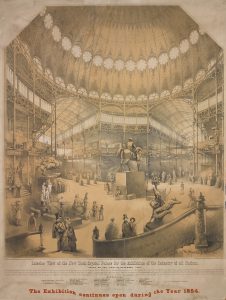

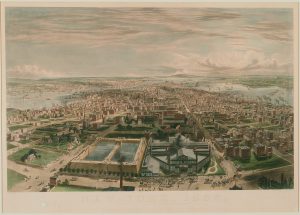

“Shadow. A first-class police officer; one who possesses naturally the power of retaining with unerring certainty the peculiar features and characteristics of persons.”

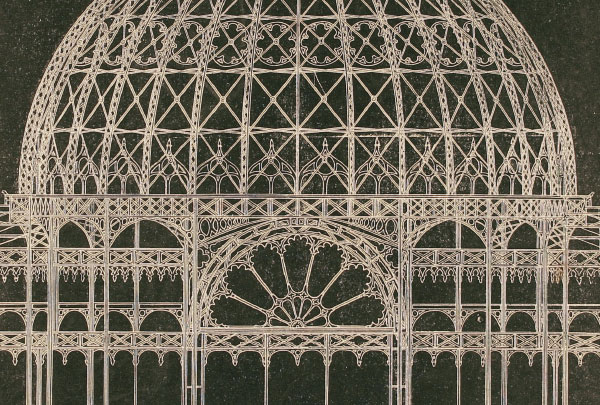

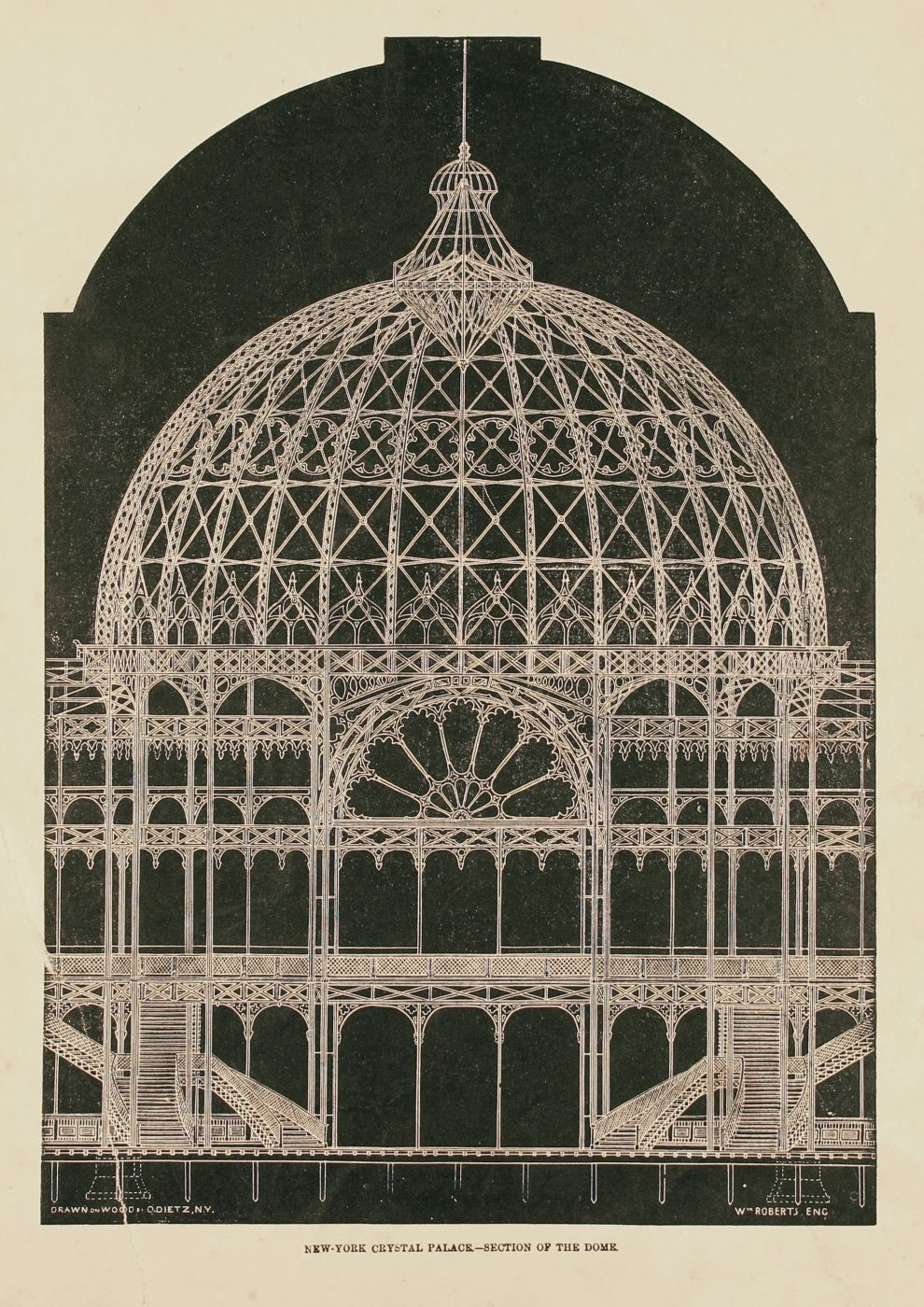

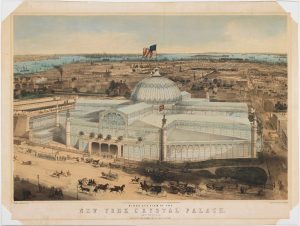

Histories of nineteenth-century New York discuss stereotypes formulated by contemporary writers and journalists, such as George G. Foster and George Wilkes, regarding the city’s reputation as both a genteel, celebrated center of commerce and culture and a degenerate urban environment.1 Nineteenth-century New York City police officers’ social role and professional duties (fig. 1), however, remain underexplored in relation to the antebellum city’s “shadowy recesses,” presumed perils, and middle-class notions of gentility.2 The sartorial history of police officers appointed to patrol the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in the New York Crystal Palace in 1853 offers unparalleled insight into policemen’s civic responsibilities during this time, which were directly linked to appearance and self-presentation within public spaces.3 How did Crystal Palace police officers patrol the exhibition, what crimes did they encounter, and what was the impact of their appearance? Foregrounding their uniform helps answer these questions and situates the exhibition as a visual microcosm of the nineteenth-century metropolis.

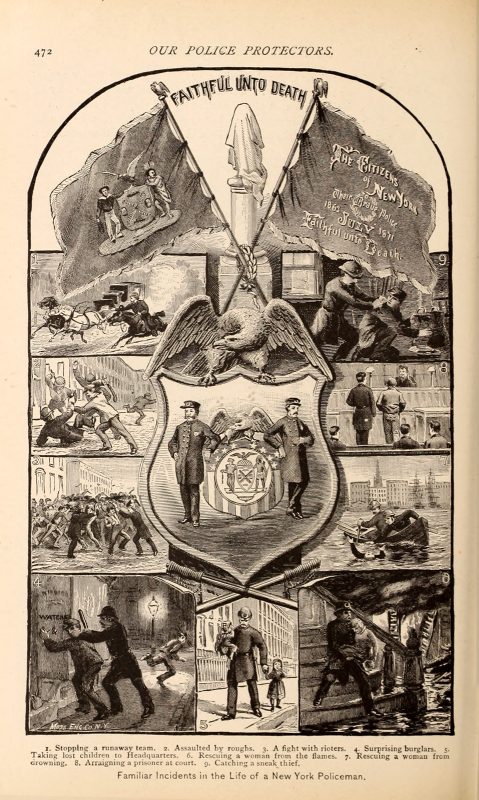

Fig. 1 Moss Eng. Co. NY. Familiar Incidents in the Life of a New York Policeman, ca. 1885 Print. From Augustine E. Costello, Our Police Protectors: History of the New York Police from the Earliest Period to the Present Time (New York: Costello, 1885), 472. Original caption: 1. Stopping a runaway team. 2. Assaulted by roughs. 3. A fight with rioters. 4. Surprising burglars. 5. Taking lost children to headquarters. 6. Rescuing a woman from the flames. 7. Rescuing a woman from drowning. 8. Arraigning a prisoner at court. 9. Catching a sneak thief.

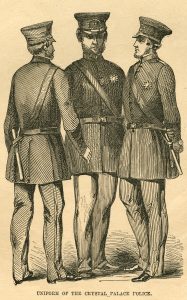

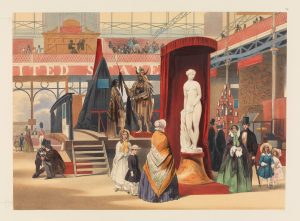

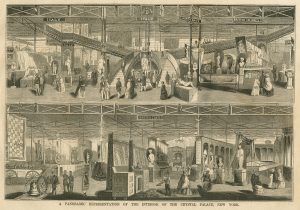

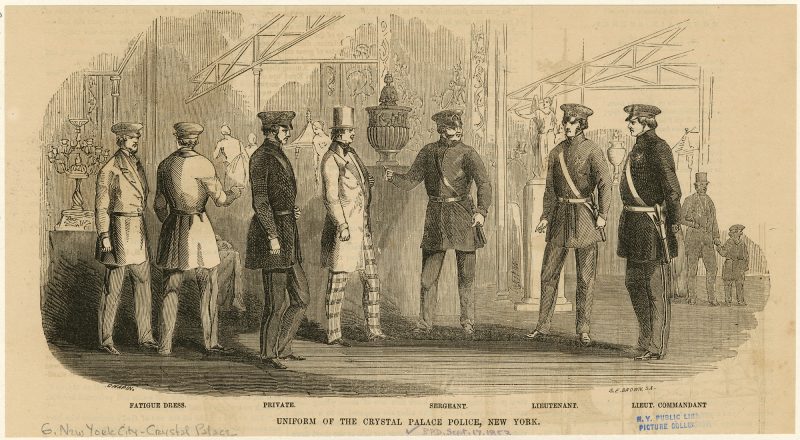

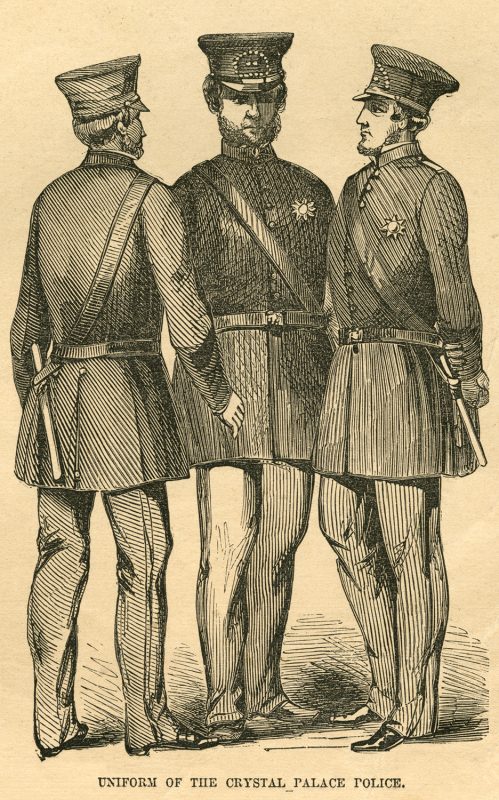

New York City police officers’ widespread adoption of regulation uniforms in the second half of the nineteenth-century was sparked by the public’s generally favorable reception of Crystal Palace police officers’ uniform in 1853. Publicizing the Crystal Palace police officers, an article from Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion provided contemporary readers with one of the first illustrations of their appearance and praised their hierarchical organization.4 Six ranked officers are depicted “in the act of spotting” a pickpocket, which the caption describes as a scene that John Reuben Chapin, the artist, “witnessed while engaged in sketching” (fig. 2.)5 The policemen wear dark blue, single-breasted frock coats, blue trousers with a narrow black stripe running down the outer side seam of each leg, leather belts with wooden clubs, leather-reinforced cloth caps emblazoned with “Crystal Palace Police,” and a star-shaped, metal badge bearing an image of the Crystal Palace. The New York Herald claimed the officers were “model police,” while Illustrated News admired the officers’ “fine looking” appearance and implied that their uniforms showcased physical and moral strength, which equipped them for their “delicate and important posts” (fig. 3).6

Fig. 2 John Reuben Chapin; Samuel E. brown, engraver. Uniform of the Crystal Palace Police, New York. From “Uniform of the Crystal Palace Police, New York: The Crystal Palace Police,” Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, September 17, 1853. Wood engraving. Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Fig. 3 Uniforms of the Crystal Palace Police. From “Police of the Crystal Palace,” Illustrated News 2, no. 31 (July 30, 1853), 47. Print. Collection of Ed Witowski.

New York City’s first chief of police, George Washington Matsell (1811–1877), appointed approximately fifty ranked police officers from the city’s police department to patrol the Crystal Palace during the day. The officers were also on duty throughout the night when the building’s “shadowy recesses” were illuminated by gas light fixtures expressly designed to facilitate twenty-four-hour surveillance.7 The Crystal Palace police force included a lieutenant commandant, two captains, four lieutenants, and four sergeants who organized and oversaw four companies of private-ranked officers. On their frock coats, more than thirty Crystal Palace police officers, including Lieutenant Commandant Robert Bowyer, wore an additional silver badge that signified former military service in the Mexican American War (1846–1848). Lieutenant William Jameson’s military training under Commodore Matthew C. Perry in 1848, for example, likely aided his role as drillmaster of the Crystal Palace policemen. Officers assigned to the Crystal Palace followed military-style exercises instituted and conducted by Jameson in a building called the “Old Arsenal,” where they were trained to maintain order within the exhibition.8

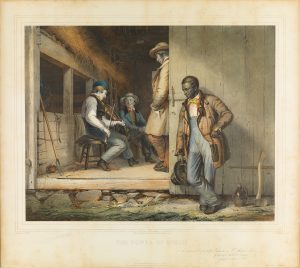

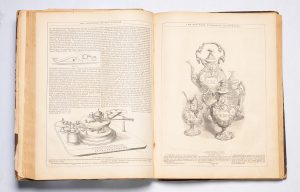

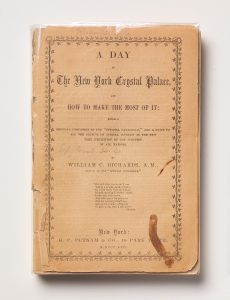

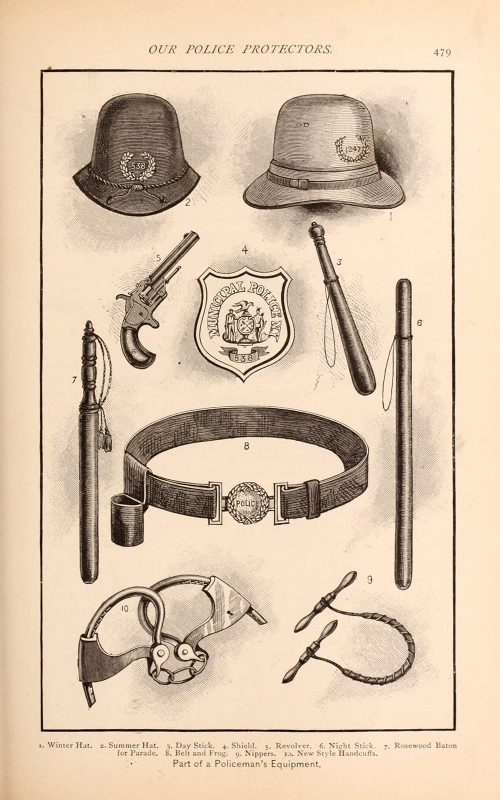

Contemporary journalists claimed that the uniforms’ resemblance to those of the American military attested to the officers’ “gallant” trustworthiness.9 William C. Richard’s popular guidebook, which was intended to lead visitors through the Crystal Palace and provide reliable information related to the variety of exhibits on display, noted the location of a “Police Office” whose entrance in Court 5 was surrounded by “architectural ornaments in vitrified clay.”10 Later in the guidebook, Richards again assured visitors of the officers’ presence and “vigilant” watch over valuable objects, which the public were urged not to touch.11 Lieutenant Commandant Robert Bowyer guarded the keys to a safe on display at the exhibition, which served as a repository for valuable jewels at night, and the diligence of one officer James Metcalf’s diligence resulted in the arrest of a German department director caught stealing jewelry, ceramics, and textiles from other countries’ displays.12 The appearance of the Crystal Palace police officers’ uniforms also reflected developments in nineteenth-century policing practices initiated by Chief Matsell in response to wider urban disorder at the time, including the authorization of New York City police officers’ first weapon, a twenty-two-inch-long wooden club, following the unprecedented violence of the Astor Place Riot in 1849. These wooden clubs most closely resemble a nightstick and parade baton depicted in a later illustration of typical nineteenth-century police equipment (fig. 4)13. A journalist describing the Crystal Palace police warned that these clubs “once applied, will make a rather marked impression.”14

Fig. 4 Augustine E. Costello. Part of a Policeman’s Equipment. From Augustine E. Costello, Our Police Protectors: History of the New York Police from the Earliest Period to the Present Time (New York: Costello, 1885), 479. Original caption: 1. Winter hat. 2. Summer hat. 3. Day stick. 4. Shield. 5. Revolver. 6. Night stick. 7. Rosewood baton for Parade. 8. Belt and frog. 9. Nippers. 10. New Style Handcuffs.

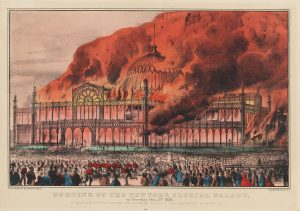

That a uniform could visually promote order and signify the wearers’ profession outside military and aristocratic British cultural constructs—such as domestic livery—was a new notion in nineteenth-century New York.15 In fact, before the Crystal Palace exhibition, many New York City police officers “‘strongly objected to wearing a specially designed uniform” viewing the uniform as ‘a British innovation and an infringement on their rights as freeborn American citizens.”’16 Some civilians also reacted violently to New York City police in uniform: “At the burning of the Old Bowery Theatre almost a riot occurred, the populace threatening to mob the police, whom they designated as ‘liveried lackeys.’” After the burning of the theatre, sympathetic city officials abandoned their ongoing attempts to outfit police in uniform, which had begun with the founding of New York City’s police department in 1845, and permitted officers to wear ordinary clothes while on duty, provided that they donned an eight-pointed, star-shaped badge on the breast of their coats.17 Reflecting on the development and evolution of New York City police uniforms, a journalist writing in the late nineteenth century claimed that the New York Crystal Palace police officers significantly shattered the negative connotations of police uniforms even though some citizens and New York City police officers persisted in responding to the uniforms with indignation and distaste.18

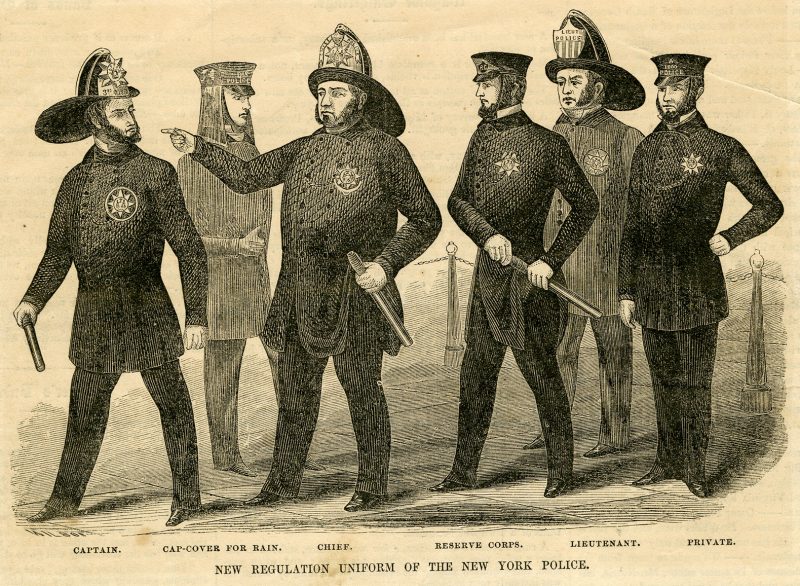

Uniformed New York City police officers assigned to work at the 1853 Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in the New York Crystal Palace forever changed the appearance of the New York City police department. Their attire, “a novelty at the time,” also enhanced the exhibition’s visual impact, “won the respect of the visitors,” and likely combatted the “nightmares of deception and obscurity” inspired by popular journalism and literature.19 Policing practices and police uniforms operated socially within the New York Crystal Palace, demonstrating how the exhibition functioned as a microcosm of an increasingly genteel, if at times disorderly, city. As a journalist announced with finality, “thus this important arm of the law for the great metropolis of America may be said to be in a state of thorough organization and complete in all its departments” (fig. 5).20

Fig. 5 New Regulation Uniform of the New York Police. From “New York Police,” Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, January 7, 1854. Print. Special Collections, Lloyd Sealy Library, John Jay College / CUNY. Joseph P. Riccio Jr. Collection of Historical Police Images.

George G. Foster and George Wilkes were popular American journalists during the nineteenth-century, known for their writings about New York City. Wilkes started publishing the National Police Gazette in 1845 after he was briefly imprisoned for libel. Wilkes sold the paper, which provided sensational and dramatized reports of crime in New York City, to George Washington Matsell, New York City’s first chief of police, in 1866. For recent discussions about Foster and Wilkes, see Stuart M. Blumin, “Explaining the New Metropolis: Perception, Depiction, and Analysis in Mid-Nineteenth-Century New York,” Journal of Urban History 11, no. 4 (November 1984): 9–38; Edwin G. Burrows, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 684; Dell Upton, “Seeing and Believing,” in Another City: Urban Life and Urban Spaces in the New American Republic (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 105. See also George G. Foster, New York by Gas Light: With Here and There a Streak of Sunshine (New York: Dewitt & Davenport, 1850), https://books.google.com/books/about/New_York_by_Gas_light.html?id=ZArVAAAAMAAJ.

Upton, “Seeing and Believing,” 105; Blumin, “Explaining the New Metropolis,” 134.

See Upton, “Seeing and Believing,” 87–110. “Social legibility” refers to an individual’s ability to read or decode the visual language of an urban environment in terms of “people and spaces” (103). Upton argues that “the legibility of people and spaces became conflated in popular culture, as urbanities found increasing numbers of both puzzling, and sometimes ominously, obscure.” The New York Crystal Palace exemplifies this bewildering nineteenth-century “conflation” of people and spaces, in which self-presentation in general and clothed bodies more specifically acted as a “medium of social interaction.” Inspiring both respect and disdain from exhibition-goers, the “bounded,” uniformed appearance of Crystal Palace police officers illustrate Upton’s claim that, “the genteel body’s tight, predictable perimeters . . . spoke of self-possession, of a clear sense of identity and a powerful agency” (95).

“Uniform of the Crystal Palace Police, New York: The Crystal Palace Police,” Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, September 17, 1853, 185.

Ibid.

“Crystal Palace—Model Police,” New York Herald, April 25, 1853, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress, http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030313/1853-04-25/ed-1/seq-4/.

How to See the Crystal Palace: Being a Concise Guide to the Principal Objects in the Exhibition (New York: Putnam, 1854), 8. The Crystal Palace police officers’ night patrol evokes themes explored by George G. Foster in his famous book, New York by Gaslight.

Cadmus Marcellus Wilcox, History of the Mexican War (Washington, D.C.: Church News, 1892), 705; Augustine E. Costello, Our Police Protectors: History of the New York Police from the Earliest Period to the Present Time (New York: Costello, 1885), 250; “Police of the Crystal Palace.”

See “Police of the Crystal Palace,” Illustrated News, July 30, 1853, 47; “Uniform of the Crystal Palace Police, New York”; “Police of the Crystal Palace”; “Crystal Palace—Model Police.”

William C. Richards, A Day in the New York Crystal Palace and How to Make the Most of It: Being a Popular Companion to the “Official Catalogue,” and a Guide to All the Objects of Special Interest in the New York Exhibition of the Industry of all Nations (New York: Putnam, 1853), 30.

Ibid., 44.

“Herring’s Patent Fire-Proof Safe,” Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, October 8, 1853; “An Important Arrest,” Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, December 1, 1853, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress, http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86092535/1853-12-01/ed-1/seq-2.pdf.

Joshua Ruff and Michael Cronin, New York City Police: Images of America (Charleston, S.C: Arcadia, 2012), 15. The Astor Place Riot was a violent attack by a large group of working-class American citizens and Irish immigrants against English actor William Macready. It was fueled by nationalistic, anti-British sentiments and spurred by Macready’s rivalry with American actor Edward Forrest. The uniforms worn by the New York City police officers who responded to the burning of the Old Bowery Theatre were modeled after British police uniforms. This visual similarity was not lost on the crowd and likely intensified the violence. The unprecedented number of injuries and casualties led to formal police training in riot control and to Matsell’s authorization of the use of wooden clubs.

“Police of the Crystal Palace.”

Lorenzo Greco, “Social Identity, Military Identity,” in Uniform: Order and Disorder, ed. Francesco Bonami, Maria Luisa Frisa, and Stefano Tonchi (Milan: Charta, 2000), 147.

Raymond W. Kelly, The History of New York City Police Department (New York: New York City Police Department, 1993), 3, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/145539NCJRS.pdf.

Kelly, The History of New York City Police Department, 3; Ruff and Cronin, New York City Police, 9. Urban legend states that these badges were often made of stamped roofing copper, which spurred New York City residents to nickname policemen “cops” or “coppers.” These terms remain in use today; however, their origin more likely relates to the verb “cop” and its past tense “copped” (meaning to capture, seize, or arrest), which emerged during this time. See Matsell, Vocabulum, 21, for a nineteenth-century definition of the word “copped” in this sense.

“The New-York Police: Interesting History of the Old and Modern Systems,” New York Times, June 4, 1871.

Ibid; Upton, “Seeing and Believing,” 104.

“New York Police,” Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, January 7, 1854, http://dc.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/index.php/Detail/Object/Show/object_id/705.